Rennie Scaysbrook | January 27, 2017

We’ve been waiting nine years for the new Honda CBR1000RR. Nine long years for the Honda Motor Company to join its two wheeled foes in the electronic age—an absolute lifetime in terms of modern superbike technology.

Old meets new. The very first Honda CBR900RR of 1992 is flanked by the latest iterations bearing the Fireblade name: the CBR1000RR (left) and the CBR1000RR SP2 (right).

Old meets new. The very first Honda CBR900RR of 1992 is flanked by the latest iterations bearing the Fireblade name: the CBR1000RR (left) and the CBR1000RR SP2 (right).

Honda has been slow coming to the party due to all number of factors, not half of which being there wasn’t a lot wrong with the 2008-2016 model. It was and still is a very good motorcycle, but the world has moved on and Honda can no longer ignore the fact sensors and giros are just as important as a good chassis and outright engine performance to producing a 21st century superbike.

The 2017 Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade (it’s called Fireblade in almost every area of the world bar North America—c’mon, American Honda, just name it so—it sounds so good), is now not just one machine. It comes in three flavors: the base model CBR1000RR (a non-ABS version will set you back $16,499/ABS for $16,799), the up-spec CBR1000RR SP ($19,999, ABS only) and the upper-spec CBR1000RR SP2 ($25,000), of which only 500 are being built, and most of those will be going straight to the racetrack—an SP2’s rightful home.

Honda has taken what was already an excellent chassis, trimmed the fat and given us a ready-made corner weapon.

Honda has taken what was already an excellent chassis, trimmed the fat and given us a ready-made corner weapon.

The full makeover

For 2017, the CBR has seen its most extensive makeover in a decade and is now laced with the game-changing gizmo in the Bosch Inertial Measurement Unit that debuted a few years ago. The IMU means traction control, wheelie control, ABS with rear wheel lift control, three stage engine brake control, five selectable power modes and an optional quickshifter are all fitted. The SP takes it a step further, with Öhlins electronic suspension the Swedish company hopes will revolutionize how we look at suspension, Brembo monoblocs instead of the standard CBR’s Tokico front brake calipers, a lithium-ion battery, a titanium muffler and, in a first for a production motorcycle, a gorgeous, ultra-light titanium gas tank.

The CBR is 0.94 inches narrower across the top of the fairing, 0.7 inches narrower at the fairing’s mid-section and 0.59 inches narrower where the rider’s knees sit.

The CBR is 0.94 inches narrower across the top of the fairing, 0.7 inches narrower at the fairing’s mid-section and 0.59 inches narrower where the rider’s knees sit.

The engine has been revamped top to bottom to provide a greater thirst for revs and top-end power without sacrificing the CBR’s legendary mid-range grunt, and the chassis has seen a nip and tuck job the actors on that terrible TV show Nip Tuck would be proud of.

The lack of girth is one of the CBR’s new aces (you can’t say trump card anymore, can you?). All told, we measured the CBR at our test facility of Portimao in southwest Portugal as 425 lbs—ready to ride. Compared to the claimed wet weight of the 2016 model, that’s a 40 lbs difference, a staggering weight reduction when you consider even a 10 lb loss is usually celebrated by the manufacturers.

The CBR SP gets a beautiful titanium muffler and in a first for a production motorcycle, a titanium gas tank.

The CBR SP gets a beautiful titanium muffler and in a first for a production motorcycle, a titanium gas tank.

Top all those changes off with all-new bodywork that’s both slimmer and far better looking with new angles, accents and colors, and you have a CBR range that’s well and truly here to play with the bikes from home and abroad that have steadily knocked it off its perch as the benchmark in the superbike category.

Honda is claiming 189hp at 13,000rpm at the crank and 84 lb-ft of torque at 11,000rpm for the new Blade. The engine itself has come in for a full work over, with a new crank, pistons, revised cylinder head, more compression, 2mm larger (now 48mm) throttle bodies and a 750rpm higher rev ceiling.

Honda is claiming 189hp at 13,000rpm at the crank and 84 lb-ft of torque at 11,000rpm for the new Blade. The engine itself has come in for a full work over, with a new crank, pistons, revised cylinder head, more compression, 2mm larger (now 48mm) throttle bodies and a 750rpm higher rev ceiling.

The chance to test this hugely important motorcycle came at one of the finest racetracks on the planet, the Algarve International Circuit, otherwise known around the world simply as Portimao, in southwest Portugal.

It’s 2.9 miles of racetrack that is never flat and only straight for about five seconds on a CBR— Portimao is a supreme test of braking ability, front end compliance, acceleration performance and, crucially, electronics.

Under brakes the CBR SP’s Brembos have plenty of bite but are held back by the ABS system.

Under brakes the CBR SP’s Brembos have plenty of bite but are held back by the ABS system.

Before we start, I will let you know, dear reader, that this CBR article cannot be expressed as just a ride and tech presentation. The electronics govern this bike to such a degree they will have their own section below, because it’s much more than just an electronic steering damper and traction control. Even the lingo has changed. It requires extra consideration.

OK, we good? First up, a good ol’ ride impression.

We had two bikes to play with—the base-model CBR fitted Bridgestone S21 sport track tires, and the SP fitted with Bridgestone V02 slicks. Normally the SP will receive Bridgestone RS10s but Honda chose to throw slicks on for our track day to try and explore the outer limits of the Öhlins Smart EC Suspension that’s exclusive the SP and SP2.

The base model CBR comes with Showa’s Big Piston Fork and Balance Free rear shock.

The base model CBR comes with Showa’s Big Piston Fork and Balance Free rear shock.

I was first out on the base model CBR and the initial feel was like meeting a buddy for the first time in a few years who has spent almost every waking second at the gym. The CBR still retained the same compact feel but dimensionally it was far slimmer across the front of the fairing, tank and seat, although the ’pegs are still a touch too high and my knees were a bit cramped. It’s still a small bike, regardless of that 1000cc badge on the fairing.

The CBR felt like the old bike, just better. The rake and trail figures are unchanged at 23°/3.8in, and the Showa Big Piston Fork was carried over from the 2016 model and provided excellent feel under braking and initial cornering on track. Portimao isn’t the bumpiest of places so it’s hard to comment as to the damping characteristics for street riding, but at a reasonable track pace the fork has a predictable performance that should suit a wide variety of riders. Go racing, however, and you’ll want to stiffen it up, pronto.

The brand new dash is super easy to read at speed and displays a ton of information. This is the base model, as down below it shows power mode (P), traction control (T) and electronic braking control (EB).

The brand new dash is super easy to read at speed and displays a ton of information. This is the base model, as down below it shows power mode (P), traction control (T) and electronic braking control (EB).

The CBR turns beautifully and with a far reduced effort from the rider. The frame and swingarm itself is marginally lighter but overall, the lack of weight overall hits you in the face like the smell of old fish and you can throw the CBR from side to side like the 600cc bike bearing the same name. You can change lines mid-corner much faster and easier than the old bike and the CBR still retains that forgiving nature, the same stability that made the old bike a contender way past its use by date. Thank god.

The base model CBR runs Tokico four-piston Monobloc calipers, which are perfectly fine for 90 percent of the riding you’ll do. There’s good feel at the lever and plenty of power to haul you up, but the ABS system cut in far too early when braking hard into turn one and the downhill entry of turn four—it was an electronic problem I would experience later on the SP with its Brembo Monoblocs, and I’ll explain the situation further in the article.

The electronically-suspended SP is indeed a step ahead of the conventionally-equipped base model CBR pretty much everywhere on the circuit.

The electronically-suspended SP is indeed a step ahead of the conventionally-equipped base model CBR pretty much everywhere on the circuit.

SP is HRC for Special…

Switching to the SP version, the big cheese here is the fitment of the latest version of the Öhlins electronic suspension system fitted to the NIX 30 fork and TTX36 shock.

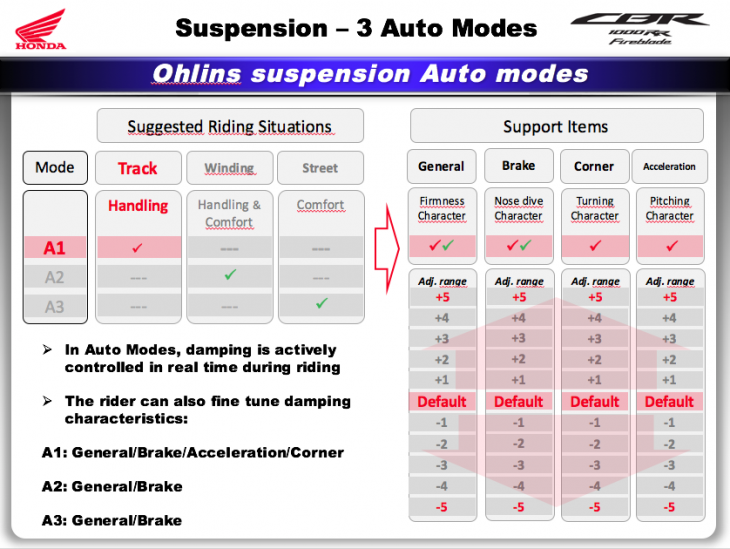

Öhlins has decided to reprogram how we view and adjust suspension. Dubbed Öhlins S-EC Suspension, it has six available modes—three auto and three manual—for your riding pleasure. In auto mode, the system monitors suspension action 100 times per second and adjusts the ride depending on the riding condition present. Within the three auto modes there are preset parameters for Track (Mode 1—racetrack), Winding (Mode 2—canyon roads) and Street (Mode 3—comfort).

This is the basic diagram for the auto mode in the electronic suspension. No such thing as a click here and a click there anymore…

This is the basic diagram for the auto mode in the electronic suspension. No such thing as a click here and a click there anymore…

Switching to manual mode, you also get three parameters, but you can save your settings for the ride condition you encounter and change on the fly. Want a stiffer setting in Mode 2? No problem. Just dial it up using the dash to whatever level (+ or – 5) you like. But here’s the crux: Honda isn’t giving you front and rear preload, compression and rebound to play with. Instead, they have broken the system down into Braking, Cornering and Acceleration, with a General map being almost like a middle ground, if you will. Whatever change you make affects both ends of the motorcycle. Dial up +5 in cornering and the bike gets stiffer everywhere. Dial in -3 on acceleration and you’ll likely squat the back-end when you get on the gas. It’s a simplified version of playing with clickers, maybe too much.

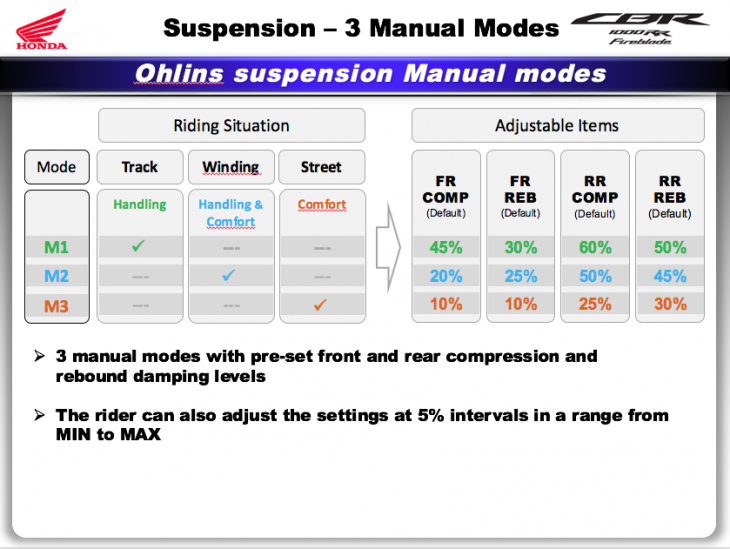

Switching to the manual modes lets you go old school to a point with front and rear compression and rebound adjustment. You still set your sag the old fashioned way with a socket on top of the fork, but the rear shock has a hydraulic preload adjuster at its base.

Switching to the manual modes lets you go old school to a point with front and rear compression and rebound adjustment. You still set your sag the old fashioned way with a socket on top of the fork, but the rear shock has a hydraulic preload adjuster at its base.

Is the ride on the SP better than the base model? Unquestionably, yes. It better be considering the price. The Öhlins system is a far better example of the future (or should that be present?) of suspension than the first electronic iterations produced for something like an early generation Ducati Panigale. It’s not like the overall ride is night and day different between the Showas and the Öhlins because the cheaper Showas are very good, it’s just that the Öhlins are slightly better everywhere, and it’s something you expect for the money you pay because, let’s face it, while a titanium gas tank is a lovely touch, I didn’t feel the difference to the steel tank when I rode it…

The SP ride was somewhat enhanced because we were riding on slicks compared to the RS10s the bike will come with. The chassis would turn a little slower but with the far superior grip of the un-treaded rubber, the ride was way more confidence inspiring, and faster.

Slick tires and a Portimao racetrack all to yourself. Not a bad way to live.

Slick tires and a Portimao racetrack all to yourself. Not a bad way to live.

However, there is one characteristic both the base model and SP bikes share: you always know where you are on the side of the tire with the 2017 CBR—that chassis feel infused into its DNA—and when you get on the gas, you’ll find the new engine is exactly as promised: more revs and more power.

Honda is claiming 189hp at the crank for their new babies but seat of the pants for me is somewhere around the 165hp mark at the wheel. That’s nowhere near the 190-odd rear wheel hp of the BMW S 1000 RR, but the Honda makes up for it in that the power comes in such a smooth, linear fashion.

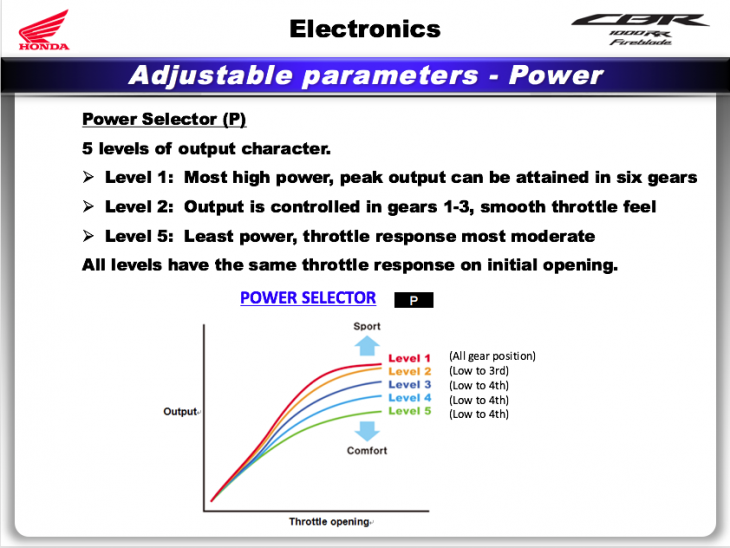

Part of this is due to the fact this is the first CBR to come with a Throttle-By-Wire system, one Honda has developed to mimic the feel of a cable throttle thanks to the return spring and various other mechanisms in the new Acceleration Position Sensor. With five different throttle parameters, you can tailor the twist grip response exactly as you like it: you can have the full engine whack in Level 1; Level 2 will limit throttle response in gears one to three, Level 3 and 4 limits throttle response in gears one to four; while Level 5 has the most neutered throttle between gears one and four, with fifth and sixth giving you engine full response. Got it?

This graph basically explains the throttle maps better than I can.

This graph basically explains the throttle maps better than I can.

Initially, I ride on Level 2 but quickly change to Level 1 because the more direct feel of the throttle to the motor is far more pleasant than having a computer telling me what I can and can’t have.

There’s still a touch of hesitation from a full closed throttle on the side of the tire, but it’s vastly improved over the 2008-2016 model and allows you to access that stonking mid-range and a top-end that makes the old bike feel like a 900.

It’s also got a wailing, screaming exhaust note that is at odds with the noise level you experience while riding. In the cockpit, the engine isn’t what I’d consider overly loud, but hearing the other journos blast past the pits between the grandstands hammered home just how much louder the new CBR is to the 2016 model. I hope to high hell the bike won’t be neutered too much when it comes to the ’States, but I’m not so sure. American Honda can’t tell me, either.

If you get an SP or and SP2, you get fancy gold wheels. They look absolutely awesome in the metal.

If you get an SP or and SP2, you get fancy gold wheels. They look absolutely awesome in the metal.

We didn’t get the chance to ride a CBR without the optional quickshifter (standard fitment on the SP/SP2), but I can report the new quickshifter equipped gearbox is a massive improvement over the old CBR. The quickshifter has three individual modes so you can vary the sensitivity from a solid lift to barely touching the lever to get your next gear, and it works in both up and down shifts, putting it on par with pretty much every other superbike available today.

On the downshift, the new slipper clutch does a brilliant job of keeping everything in line and allowing you to get on with the job of stopping the motorcycle without worrying about the back-end skipping and wondering around the racetrack. The feel at the lever is lighter than before, but seeing as I only touched the lever twice when exiting and entering pitlane, I’ll reserve final judgement until the road test.

Portimao’s massive undulations highlighted a surprising feature in the Honda electronics…

Portimao’s massive undulations highlighted a surprising feature in the Honda electronics…

Mechanically—as in engine and chassis—the new CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP are excellent machines. Less weight and more power is always a good practice when it comes to creating a real, modern day superbike. It has an excellent chassis and the motor has plenty of mumbo with the top end we’ve been waiting for.

But there’s one part of the equation we’re yet to talk about.

Electronics for days. And days. And days.

This area is the main talking point of the new CBR1000RR range. Criticized in the past for having no more electronics than fuel injection and the company’s heavy Combined ABS system, the CBR now has everything the others have and more, but it’s not as straight forward as slapping on a traction control system and hoping for the best. Oh no…

The CBR’s lost a visible amount of weight since the 2016 model. Pity we can’t say the same about the tester!

The CBR’s lost a visible amount of weight since the 2016 model. Pity we can’t say the same about the tester!

Honda has developed a whole new electronics package for the CBR based off the RC213V-S, which in turn is developed from Repsol Honda in MotoGP. Yes, the CBR does use the Bosch IMU, but it uses it differently than Yamaha or Ducati, for example.

Honda’s electronics combine traction and wheelie control functions. That is an ultra-important point because since the Bosch IMU was released, the manufacturers that used it on superbikes separated the traction and wheelie parameters, allowing you to vary them independently. Honda chose to combine them, and herein lies an issue.

The SP dash. The electronic suspension here is set to manual, as can be seen by the “MB” on the dash.

The SP dash. The electronic suspension here is set to manual, as can be seen by the “MB” on the dash.

Under the acronym HSTC (Honda Selectable Torque Control), the system calculates the throttle input, lean angle, and the rate of slip from the rear wheel to determine how much gas you’re allowed to have and ultimately, how hard you can drive out of a corner. There are nine different levels of traction control, yet the linked wheelie control has three modes: Level 1 (aimed at track riding) provides a reduced wheelie control input in TC modes one to three; Level 2 wheelie (for fast canyon riding) provides more wheelie control in TC levels four to six; and Level 3 wheelie control (for normal street riding) allows next to no lift at all in TC modes seven to nine.

Portimao compounds issues because you can spin the rear wheel like mad and wheelie into next week thanks to the undulations of a racetrack situated between three separate canyons.

Preload adjustment on this electronic Ohlins shock is done at the base. No hammers and screwdrivers anymore.

Preload adjustment on this electronic Ohlins shock is done at the base. No hammers and screwdrivers anymore.

The entry onto Portimao’s front straight is three, long, separate right hand apexes, all while going downhill, leading to a massive hump onto the straight proper. The wheelie control at this section of the track is an issue because when the front wheel comes up, it comes up hard—the HSTC electronics allow for a big, short distance wheelie, but then cut the ignition viciously, slamming the front wheel to the ground.

The problem here is not that the wheelie was cut. It is the fact that the system uses only front and rear wheel speed to detect if a wheelie has occurred, rather than the front and rear chassis pitch rate. On something like a Yamaha YZF-R1, the wheelie control can be programed in to allow you to keep the throttle pinned and have power still being transmitted to the rear wheel, with minimal drive lost as the system slowly brings the front wheel back to earth.

See that little orange “T” circled in the top left corner of the dash? That’s the traction control light coming on at over 240km/h. The CBR wasn’t spinning, but it wasn’t driving, either, as I waited for the front and rear wheel speed sensors to sync up and the light to disappear.

See that little orange “T” circled in the top left corner of the dash? That’s the traction control light coming on at over 240km/h. The CBR wasn’t spinning, but it wasn’t driving, either, as I waited for the front and rear wheel speed sensors to sync up and the light to disappear.

On the CBR on Portimao’s front straight, at 140mph it took the best part of two seconds before I was allowed to have any drive after the wheelie came. This was due to the time it takes for the front and rear wheel speed sensors to sync back up, and the ECU shutting the throttle bodies. Nothing was happening at the twistgrip, only the traction control light flickering on the dash until it disappeared and drive was restored. It was a wholly frustrating experience because it didn’t need to be like this, and strange because considering the Honda runs an IMU—the same as many other manufacturers—they seem to have deliberately altered one on the IMU’s inherent strong points in having wheelie and traction separate and independently variable.

The only way around the anti-wheelie issue is to go old school and turn the system off completely. But turning the anti-wheelie off means you also turn traction control off, and while it’s nice to drift and slide a superbike, having that protective net of traction and wheelie control removed is not a great thing.

A track mode for the ABS would be a very welcome feature.

A track mode for the ABS would be a very welcome feature.

Another electronic issue reared its head in the braking department. Remember when I said the ABS pulsing was badly? Well, this was due to the Honda Rear Wheel Lift control algorithm. The system uses the IMU to determine, via acceleration in the direction perpendicular to lift (take a pair of scissors and open them 45°, imagining the lower blade end is the front wheel and the top blade is the top of the fairing) if the rear wheel is in danger of coming off the ground under braking.

Under hard braking like the downhill turns of one and five at Portimao, the system would pulsate pretty violently, so much that on one corner entry it knocked the pads back enough for me to blow the corner.

Regardless of the electronic issues, the CBR is still a great bike.

Regardless of the electronic issues, the CBR is still a great bike.

A simple fix would be just to turn the system off, right? Well, you kinda can’t do that. I say that because when I cornered Honda’s Model Evaluator and Test Manager, Kyoichi Yoshii, as to how I would turn the system off and prevent the pulsing, he said I was unable to do so. But later he did say, in a roundabout way, that there is a way of doing it. How? Was it in the dash? The ECU? Pulling the fuse? Again, he remained silent, only giving me a wry smile. So I was stuck with ABS on. Frustrating.

They system’s action is annoying because the brakes themselves, both the base-model Nissin and SP’s Brembos, are very good units with plenty of power and feel. It’s just that they are being held back by the electronic bungey cord.

Mechanically, the CBR is awesome, and the electronic issues only show up under extreme track riding conditions. But hey, it is a superbike, after all.

Mechanically, the CBR is awesome, and the electronic issues only show up under extreme track riding conditions. But hey, it is a superbike, after all.

The 2017 Honda CBR1000RR is thus a bit of a conundrum.

The CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP2 both have a sublime chassis and an engine that while not being the fastest 1000cc lump out there, is certainly worthy of the superbike name. There’s buckets of mid-range torque and now a top-end that wasn’t available on the old machine, plus the way it transmits the go to the ground is velvety smooth.

It also (in my opinion) looks amazing. It’s a refined version of ’Blades gone by, with lovely accents, angles, lines and colors that give the bike a thoroughly modern look.

But the electronics—on a racetrack at least—are odd in their application. Under the extremes of hard track riding, the linked anti-wheelie and TC program is a strange feature. It’ll probably be fine for 95 percent of road riding situations, where Honda is aiming the base and SP models, and the electronic suspension settings will likely enable more riders to vary the front and rear in greater confidence than previously.

The CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP. Aside from the Ohlins goodies, plus some lightweight parts like the titanium exhaust and tank on the SP, they are almost identical.

The CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP. Aside from the Ohlins goodies, plus some lightweight parts like the titanium exhaust and tank on the SP, they are almost identical.

There is a way around this problem: be one of the race teams that Honda deems worthy of receiving the HRC race ECU, which has different parameters for wheelie and traction control. The race ECU is something you can’t buy, only leased by Honda. So that rules out 99 percent of CBR buyers.

The CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP motorcycles are indeed fine machines, electronic issues aside. Having switchable ABS and separate traction and wheelie control maps would be a massive boon for the machine. But still, it’s fantastic to see the Big H back in the superbike game.

Specifications

2017 Honda CBR1000RR and CBR1000RR SP

Engine: Liquid cooled, fourstroke, 16valve, DOHC in line four

Displacement: 999cc

Bore x stroke: 76 x 55mm

Horsepower: 189 @ 13,00rpm (claimed)

Torque: 84 lb-ft @ 11,000rpm (claimed)

Compression ratio: 13.0:1

Fuel system: EFI. Five variable throttle modes

Exhaust: 4 into 2 into 1

Transmission: Six-speed gearbox. Optional quickshifter on base model, standard fit on SP.

Chassis: Aluminum composite twin spar

Front suspension (base model): 43 mm fully adjustable Showa Big Piston inverted forks. 120mm wheel travel.

Rear suspension (base model): Fully adjustable Showa Balance Free shock. 138mm wheel travel.

Front suspension (SP model): Öhlins NIX30 43mm inverted fork with Ohlins Smart-EC control. Preload, compression and rebound damping adjustable.

Rear suspension (SP model): Öhlins TTX36 rear shock with Ohlins Smart-EC control. Preload, compression and rebound damping adjustable.

Front brake (base model): Dual Tokico four-piston, radially mounted calipers. 320mm disc. ABS

Rear brake (base model): Nissin single piston caliper. 220mm diameter disc. ABS

Front brake (SP model): Brembo radially mounted Monobloc four-piston caliper. 320mm disc. ABS

Rear brake (SP model): Nissin single piston caliper. 220mm diameter disc. ABS

Front tire: 120/70ZR17 58W

Rear tire: 190/55 ZR17 73W

Rake: 23.3°

Trail: 3.8 in

Wheelbase: 55.3 in

Seat height: 32.7 in

Fuel capacity: 4.2 gal

Weight: 425 lb. (wet, measured).

Color: Red/Black, HRC Tri-Color

MSRP: $16,499/$16,799 for ABS model (CBR1000RR). $19,999 for CBR1000RR SP. ABS only.