Michael Scott | November 9, 2016

We all know what GP racing means. It’s the pinnacle of achievement in every sphere. The riding, of course, but also the machines, tires, fuel, oil, etc., and circuits. It is an aspiration towards excellence. Progress must always strive towards perfection.

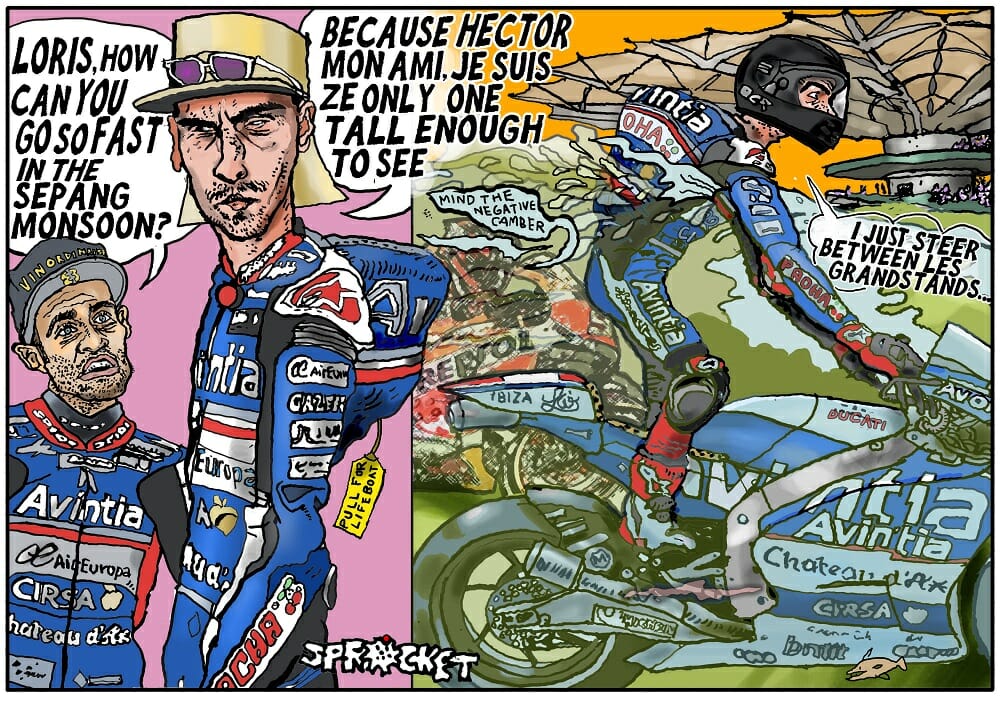

Thus it was a bit surprising to see the changes at Sepang. A major revamp included a fine new surface, better safety with paved run-offs and revised gravel traps, and improved drainage for the tropical cloudbursts. Plus, a final hairpin that had been given a significant range of adverse camber. In other words, banked the wrong way, with the greatest new elevation right at the clipping point just after the apex. The opposite of what you might think of as an improvement.

There were two reasons for this, according to track re-designers Dromo. One was to cut speed onto the front straight and thence into the first corner, which has limited run-off. Given the way a MotoGP bike accelerates, especially if it is a Ducati, that’s pretty marginal—an opinion shared by 2017 Ducati recruit Lorenzo. When a slower corner was introduced at Catalunya this year after Salom’s fatal crash, it actually led to higher speed by the end of the ensuing straight, because it allowed a less compromised throttle opening.

The other was to mess up the ideal line, giving choices of different ways to take the corner and, in theory, more overtaking opportunities. They must have had F1 in mind, because for the bikes that final hairpin has never been particularly lacking in this area, and many races have been decided last time through that corner. Although not this year.

But it makes one think about developments that instead of getting closer to perfection, are actually aimed in the other direction.

Like making worse tires, a not infrequent suggestion over the years, with the intention of making the racing more entertaining by giving the rider more to do. The idea being that if the tires lost grip early on and everyone was sliding around, it would encourage a special kind of riding skill and reward the spectators, as opposed to the sterile sight of one-line corners and smooth perfection.

There might have been some merit, for at one stage, the suggestion at GP level was inspired by the supposedly more enjoyable world superbike races, then running on control Pirelli tires that fell short of the performance of the Michelins, Dunlops and latterly Bridgestones developed almost race by race in a costly grand prix tire war.

One proponent was this year’s star Cal Crutchlow, recently moved over from SBK, and having a rather torrid time with tires that gripped so hard that if they did let go they’d precipitate a massive high-side. He preferred a lack of grip to having too much.

Another is the notion of putting all competitors on not just the same engine, but a relatively humble production unit, lacking such racing refinements as highly tunable fuel-injection and so on, and (more importantly) without cassette-style gearboxes with a multiple choice of ratios. Make it fairer, and ease the burden on both riders and mechanics.

That one actually happened in Moto2, where sleek full-race chassis are draped around porky CBR600 engines, in a lower state of tune than those used in Supersport 600. A good idea? I have always thought the opposite—the bikes are over-tired and underpowered, no recipe for greatness. But Moto2 does have its fans, especially among team managers who don’t have to pay for exotic engineering.

Then how about dumbed-down electronics? That’s another one that has happened, with MotoGP teams all using not just the same Magneti Marelli hardware, but this year also standardized software. On balance, it’s contributed hugely to closer racing. But detracted as massively from any role racing might have played in meaningful electronic research.

Here’s one they haven’t done yet, although it too has been spoken about at high level: adding weight ballast to slow down riders who win too often. It would have to be done either race by race, or more fairly by accumulated championship points. The more you have, the more lead sinkers are cable-tied to the chassis. Marquez would need a big concrete block.

If that really worked properly, then all riders would end up the season on equal scores. And wouldn’t that be wonderfully fair?

A bit like clapping leg irons on the best dancers in the Bolshoi ballet, to make it a bit fairer on the clumsy ones.

Thankfully it hasn’t happened. Yet.

And that crazy tip-tilted final hairpin at Sepang? Actually it turned out okay. After all, that sort of thing happens on real-world roads, too. And anything that makes tarmac racing more relevant to the real world can only be a good thing.CN

To read this in Cycle News Digital Edition, click HERE