Larry Lawrence | November 30, 2016

Phil Schilling, Reno Leoni, Udo Gietl, Pops Yoshimura and Rob Muzzy were among the small cadre of tuners who became living legends by way of producing many of the iconic AMA Superbike racing machines of a golden era that lasted about a quarter of a century. And so it was with Eraldo Ferracci. Ferracci emerged from the world of drag racing and went on to become one of the last in a long line of Superbike tuners who became every bit as famous as the riders who raced the motorcycles they built. Builders like Ferracci were the final vestiges of a century-long tradition of motor men who knew every inch of their racing machines. They would build and modify parts, often by hand, that would almost magically produce better power, handle and stop better or increase reliability.

By the mid-1990s the vast mechanical skills and knowledge held by tuners like Ferracci gradually diminished in the age of computer design and electronics. Now the behind-the-scenes heroes of racing teams are as likely to be a team of engine management, suspension and frame programmers, who each know one very specific, but in this day and age supremely important segment of making a motorcycle faster around a racetrack. But the romantic era of one-man in overalls holding wrench, that produced legends like Ferracci are history.

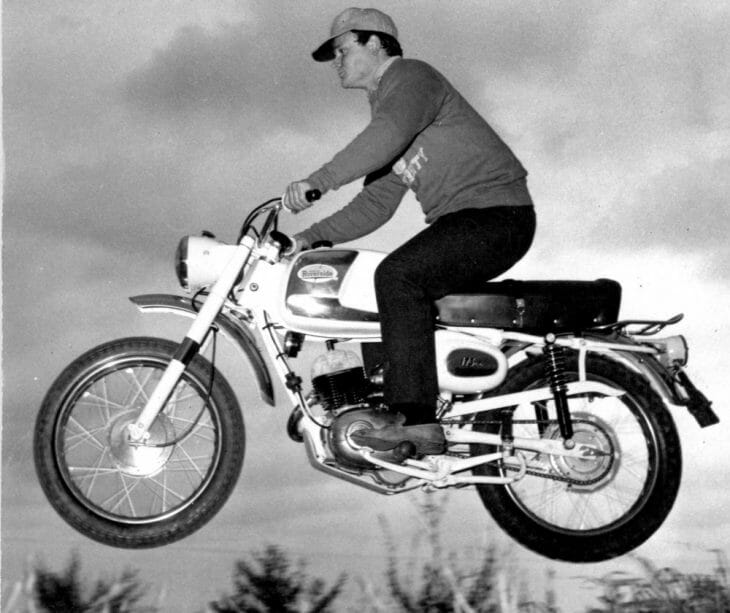

We have the now defunct department store Montgomery Ward to thank for bringing Ferracci to America. Ferracci was an engineer at Benelli in the mid-1960s and they company wanted to break into the American marketplace. Ferracci and some colleagues from Benelli were sent over survey the market and help devise a plan.

“We saw kids riding minibikes all over the place,” Ferracci recalls. He and his colleagues returned to Italy and for weeks, after regular business hours, they set about quietly building a Benelli minibike targeted to the American market. The little machine Ferracci helped design eventually sold in Montgomery Wards, JC Penney, Sears, W.T. Grant and a few other major department stores at a clip of 45,000 units in the first two years. “It was incredible,” Ferracci smiles when thinking how quickly the Benelli minibikes and scooters went from concept to showroom floor.

Interestingly, the Benelli minibike project Ferracci was instrumental in helping launch, almost got him canned.

“One night we were working (on the prototypes) and the big boss Giuseppe Benelli, he was like 80 years old, came around and was peeking around the shop. The next day the chief of the staff called me into the office and said, “What are you f*%^#! guys doing? What are you making, toys for little kids?” I told him, “No, no, we’ve got a secret project approved by Luigi Benelli for the U.S. (Ferracci laughs) The old man wanted to fire us!”

After the wildly successful launch of the small Benellis into the American market, Ferracci was once again sent back to America, this time to train the auto mechanics at the various department stores how to repair the bikes.

The intention was for Ferracci to stay just long enough to fix the backlog of broken bikes that had stacked up and train the department store automotive center mechanics on repair and then head back to Italy. But just before he was scheduled to go back to Italy, Marco Benelli came to Philadelphia to visit and told Eraldo, “I’ve got good news and bad news.” The bad news was that Benelli had been sold to De Tomaso and according to Marco, the factory and Benelli headquarters were in chaos. “Marco told me I had a good job here and it would be better to stay in America, because so many people in Italy were being fired.”

Ferracci saw the handwriting on the wall and began to seek other opportunities. Interestingly, he nearly landed at Harley-Davidson’s racing department, then being run by Dick O’Brien. “I flew to Milwaukee and they wanted to hire me, but it was only $100 per week.” Ferracci explained. “O’Brien told me it was no problem, that I could live comfortably in Milwaukee for that much. So, I said OK, I’ll do it.”

But when friends in Philly heard Ferracci might be leaving they quickly found him a job at a local shop paying him over four times what Harley offered, just to keep him in the area. Ferracci never made it to Milwaukee. “Even when I was working for Benelli, I would fix bikes for my friends and more and more people were coming to me because they liked my work. So, I was thinking about doing my own thing anyway.”

By 1980 Eraldo established Fast by Ferracci.

Honda was well aware of Ferracci’s reputation at Benelli and quickly pegged him to consult them, working out of Honda’s massive New Jersey warehouse. “I started racing Honda’s and that’s what led me into doing what I do today,” Ferracci said.

Ferracci, who as a young man was a up-and-coming road racer before the factory saw his talent as a builder and pushed him to quit racing to focus on component design, suddenly was racing again on the drag strips of the East Coast and he quickly became one of the leading Funny Bike racers, winning a slew of championships. By the mid-1980s with speeds approaching 200 mph, Ferracci was on one of his drag bikes when at 160 mph the wind caught underneath the bike and lifted the front end completely off the ground. “I told my son that I had to get off these things right now, otherwise I was going to get hurt,” Ferracci smiles.

But the custom building Ferracci had honed all his life really hit a peak with the wide-open world of drag racing. He became famous for the mechanical fuel injection he designed, among many other state-of-the-art racing components.

Vintage motorcycle racing began skyrocketing in the mid-1980s and Ferracci’s performance shop quickly became the go-to place for vintage riders on all brands to have parts made and to get their bikes prepped for racing.

Soon riders on Ferracci-prepared motorcycles were cleaning up in AHRMA racing events and Ferracci machines dominated various class championships. By way of vintage racing, Ferracci soon began being a regular presence at AMA road racing nationals, prepping the bikes of Battle of the Twins competitors Pete Johnson and Kurt Liebmann. Ferracci machines were instant winners in the Battles of the Twins GP2 class and Ferracci’s long and fruitful term inside the AMA Pro road racing paddock would make him a legend.

Next week we will pick up on Ferracci’s story as he and Ducati establish a great relationship that would eventually lead to revolutionizing the machines raced in AMA Superbike.