Alan Cathcart | January 13, 2016

A Triumph employee for 28 years, Stuart Wood and his team are the ones responsible for ensuring the Bonneville legend lives on.

A Triumph employee for 28 years, Stuart Wood and his team are the ones responsible for ensuring the Bonneville legend lives on.

John Bloor himself aside, Triumph’s head of engineering Stuart Wood, 51, is almost certainly its longest serving employee, a 28-year company veteran who joined the design team in 1987 three whole years before the appearance a quarter of a century ago of the first three and four-cylinder models bearing the revived British brand’s historic badge. He was there when the born-again Bonneville made what for many customers was a belated debut in 2000, when Bloor decided he’d re-established Triumph sufficiently well as a thoroughly modern mainstream manufacturer which could now afford to look in the rear view mirror of history by introducing a modern interpretation of its most iconic Swinging ‘60s model. Fifteen years on from there he’s headed the development team which has now once again reinvented the Bonneville, making the chance to talk to him at Valencia after a day’s ride together on the fruits of his team’s hard work all the more apposite.

Stuart, when did you and your guys in Triumph R&D start work on this born again version of the born again Bonneville?

SW: The first discussions took place about four years ago in 2011, when we knew that with Euro 4 coming in we were going to be working on either an update of the existing bike, or an all-new model. We saw the original styling proposal in May 2012, and it all moved on from there.

So Euro 4 was the trigger for creating what we’ve just been riding?

SW: It was initially, in that one way or another we were going to have to hit tighter emissions and noise targets, and incorporate ABS as standard. But by the time you’ve repackaged and updated the existing model to incorporate that, you’ve almost redesigned the whole bike anyway, so the opportunity was always there to do something more with the range by developing a 1200cc version which we really thought would be wanted by customers. So we took the opportunity to build an all-new engine platform that would allow both 900cc and 1200cc versions..

A low center of gravity and revamp ergonomics makes for a very engaging ride.

A low center of gravity and revamp ergonomics makes for a very engaging ride.

Essentially, is there any part of the new engine that’s a carry-over from the old one?

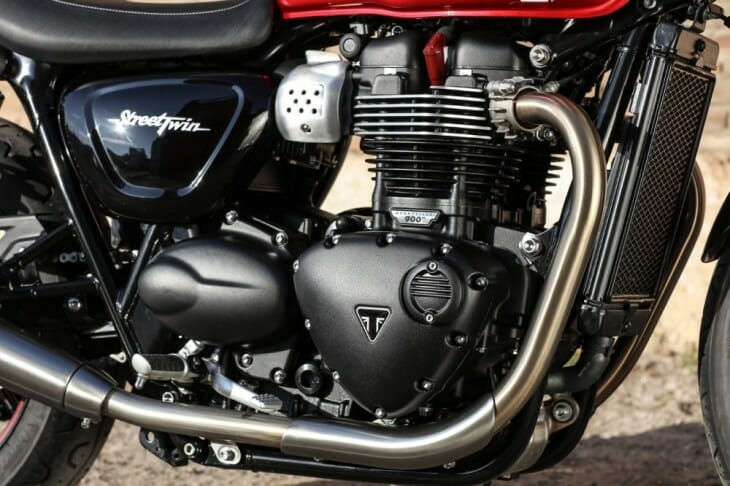

SW: I was going to say no, but there may be a nut, bolt or washer in common – but nothing else! Really, there was no intention to carry anything over at all, although obviously the basic architecture is essentially the same, which is driven by the visual layout of the engine. But there are some fundamental differences, the main one being the fact that it’s liquid-cooled, although from the outside of the bike no-one would tell the difference. We’ve always strategically cooled the cylinder head via an oil cooler, but now we have water cooling instead to also cool the cylinders. Of course, the fins are still doing some of the work, but the metal temperature is not as high as if it had been air-cooled.

That’s allowed you to downsize the radiator, which is extremely well disguised!

SW: Interesting word, that – because when you say disguised, we have in fact done the exact opposite! We haven’t put shrouds around it, we haven’t tried to cover it up – we’ve just mounted an honest radiator in full view and packaged it the most sensible way, which is two tanks top and bottom so we can take the water hoses directly to the engine at each end, so you don’t see any plumbing. It’s all internal waterways in the engine, with very short external rubber hoses for a clean appearance.

What other considerations did you have in designing the new engine?

SW: The fact that it was going to be 1200cc as well meant we had to design the whole engine with that in mind. The 1200 has a bigger bore, a different cylinder head, and we’re running a decompressor as well on that but not on the Street Twin, where the layout is the same and the crankcases are identical.

Keeping the engine height down was important with the extra capacity of the new Bonnie.

Keeping the engine height down was important with the extra capacity of the new Bonnie.

When riding it the engine’s incredibly smooth, even more so than the old T100 Bonneville. Have you got a different counter-balancer arrangement?

SW: The mechanical strategy for primary balance is exactly the same, with twin gear driven balance shafts front and rear which rotate in the same direction as one another, but in the opposite direction to the crank. So the engine is 100 percent primary balanced, and because we wanted a more refined engine, we’ve gone for a 270-degree crank now on both 900 and 1200 versions, which gives you full secondary balance naturally. It’s important the engine should seem more refined in terms of vibration – nobody wants mechanical vibrations nowadays masquerading as ‘character’. You want some character, you want to feel the firing impulses, but not at the expense of undue vibration. So a 360-degree motor was never on the cards – sorry, purists, but it was time to move all the bikes to 270, and we have a lovely exhaust sound which is pretty refined.

The bike indeed sounds glorious when you’re riding it. Was that one of your key targets, and how did you succeed in doing that despite the restrictive noise requirements of Euro 4 which has forced some other manufacturers to mount really intrusive and heavy exhaust systems?

SW: I’ll admit it took a lot of hard work just constantly experimenting with different exhaust systems on a trial and error basis. The guys did some predictive work on sound quality as well as quantity, but when it comes down to it actually building exhausts and trying them out is how you get it right. So many of our engineers ride bikes, they completely get what we’re looking for, not just in sound.

What other parameters were key to designing the new engine? You’ve got fantastic fuel economy – was that a target?

SW: Everything comes together to give the fuel consumption figure. We’ve gone for a ride by wire throttle, and that’s enabled us to get the responsiveness from the engine while meeting increased emission restrictions yet with good fuel economy, plus all the bikes now have switchable traction control as standard.

Little design touches like showing off the spark plug caps keep the new model’s links with the past.

Little design touches like showing off the spark plug caps keep the new model’s links with the past.

With ride by wire on board why not have different riding maps, especially one for wet weather?

SW: Not on this bike. We wanted to keep it as a really accessible model, very easy to ride and easy to get on with, so we’ve kept the Street Twin very straightforward. But when we launch the other four Bonneville models this year you’ll see there’s more rider aids on them than on this one.

What other considerations were important at the design stage?

SW: One thing we really wanted to do on the layout even with the larger capacity version is to keep the engine height down. So fixing the bore and stroke was the driver for that – if you can get the stroke shorter then you can have shorter conrods, and everything shrinks quite a lot. Basically, the bore and stroke we’ve chosen and the cylinder head packaging have kept the engine height down, so we’ve gone to a single overhead cam rather that a twincam design, with the chain at the top and gear at the bottom – we didn’t want a large chain run at the top sticking out of a nice cam cover. Another benefit from the single cam is the aesthetics of the cylinder head, because what we’ve done is to expose the two outer cylinder head bolts on either side, and we’ve got vertical fins there as well which are all fairly evocative as sort of borrowed from our heritage. Obviously you’ve got your spark plugs and spark plug caps on show as well, so it makes the whole top of the engine look really pretty in a traditional way.

That extends to the throttle body, which you’ve made resemble a carb.

SW: Yes, it’s just a single 38mm throttle body on this one, but twin bodies on the 1200, and that’s all about tuning the engine the way we wanted it to behave. We knew from talking to our customers and people who aren’t our customers but might be, that for this bike the maximum power figure didn’t matter so much, because what people want is torque and drivability in the part of the rev range they’re used to using, which is bottom to midrange. So what we went for was more power and torque in the midrange, and once you’ve made that decision you can then optimise throttle body size and port size to flow correctly at that point in the rev range. That way we can get higher gas velocity and better mixing within the cylinder, and thus cleaner combustion which gives the rideability people are looking for.

It’s most noticeable when you ride it how much more torque there is low down, especially compared to the old Bonneville.

SW: Absolutely, and improved response, too. Keihin are great to work with – their contribution is key to this.

A new seat makes long days much more comfortable.

A new seat makes long days much more comfortable.

The Street Twin has a five-speed gearbox – why not a six-speeder with a smaller capacity engine which needs to be rowed along more on the gearbox?

SW: We’ve got a six-speed on the 1200, but again the Street Twin is a nice, nippy, rideable bike which feels more appropriate with a five-speed transmission and nicely spaced gear ratios.

When you sit on the bike it’s immediately apparent that you’re sitting pretty low down – presumably thanks to the reduced height of the engine you spoke about earlier. But the whole bike seems pretty low to the ground, even if there are no ground clearance problems at respectable angles of lean. Was it a conscious decision to try and get a low cee of gee?

SW: Absolutely. The whole bike had to be manageable, and to achieve that you’re looking at a complete package where everything has to work together. So from the outset it’s all about ergonomics – when you’re designing a bike ergonomics, geometry and weight distribution are the three main targets initially, and how you go about controlling that with suspension, brakes, wheels and tire sizes, is the next stage. But the fundamental layout was always about trying to get that sense of manageability. With this model, the 900, we’ve made the riding position slightly more engaging, so we want the rider to sit forward into the bike, and be part of it, whereas on the T120 there’s more of an upright relaxed position. On the Street Twin we wanted it to be a more engaging stance, so we’ve allowed enough space for the rider to move around. We’ve had many taller guys saying it’s perfectly comfortable – just move back on the seat if you want more room, because there is place to move about. Ergonomics rule!

Just because a bike has classic styling, it shouldn’t be compromised when it comes to developing the chassis and providing good handling. From the dynamic point of view we targeted the character, feel and performance we wanted for each of the new Bonneville models, especially to incorporate the agility that our bikes are famous for, and to get the neutrality and stability our customers want. On the Street Twin we’ve focused on making it more accessible and fun to ride, without being in any way demanding of the rider.

18 inch wheels get wrapped in specially developed Pirelli rubber.

18 inch wheels get wrapped in specially developed Pirelli rubber.

Why fit an 18-inch front wheel, when the previous cast-wheel Bonnie had 17-inchers front and rear?

SW: Partly aesthetics – we’ve tried to be as faithful as we can to the looks of the original Bonneville, and I think we now have a more elegant model than before. When you put them side by side you can see the purer line and stance of the new bike, and wheels and tires are a part of that. Pirelli put a lot of effort in working with us on tyre development as well, producing numerous prototype tires for us to evaluate. That’s what it takes to make the bike as good as it can be, and it’s great to have partners like that.

You and your guys produced the first born-again Bonneville in 2000, and here you are redoing it in 2015. That’s a 15-year span, so are you expecting this one to have a similar long shelf life?

SW: It would be nice, because it’s a bike with timeless styling and character. The thing about having to recreate or redesign an iconic product is that people think it’s easy – well, you’ve already got that design there to copy, so what’s the problem? In fact, the amount of engineering and aesthetic design work that goes into being faithful to the original iconic model while packaging a thoroughly modern motorcycle incorporating all the technology which by definition you can’t put on display because it’s modern and right up to date, means there’s that much more work entailed in taking it to the next stage than having a free hand to come up with whatever you like without the restrictions of the previous model. But it’s a lovely challenge, and I think the reason why developing the whole Bonneville range down the years has been such an involving project for our design and manufacturing people, and why everyone who’s been involved with this redesign has enjoyed it, is because we’ve had to deliver something that’s beautiful while paying due respect to the model’s traditions, as I believe these new bikes do.

We started out with the intention of building a range of Bonnevilles for the 21st century – not any kind of a pastiche, but a real Bonneville for today’s roads that draws from the DNA of the model down the years to make it more beautiful and desirable, particularly in the detail. Porsche have always been masters of doing this with the 911 family, and I hope people will consider we’ve done something comparable with these new Bonneville models. We were actually lucky enough in a way that we needed to incorporate new technology on it to meet Euro 4, and so we redesigned it in a way which I believe has made it a much improved bike that looks better, rides better and is obviously completely up to date, technologically speaking. So let’s see how that handles the passage of time!

The vastly expanded family of Bonneville machines is a very impressive line up.

The vastly expanded family of Bonneville machines is a very impressive line up.