History on Wheels

This exact motorcycle is the most valuable ever sold at auction. On January 25, 2018, Australian collector Peter Bender paid a staggering $929,000 at the Bonhams Motorcycle Auction in Las Vegas for this Vincent Series C Black Lightning, piloted by Jack Ehret to two Australian speed records and numerous race wins in the 1950s and ‘60s. Alan Cathcart takes up the story.

More than six decades ago, the Vincent Black Shadow delivered the most performance from a street-legal vehicle that money could buy—on two wheels or four. Officially timed at 122 mph, it outpaced the Jaguar XK120 two-seater, then the world’s fastest production car, making the Shadow the first true Superbike of the modern era.

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Photography by Kel Edge, Jim Scaysbrook Archives

The ultimate Vincent was the Series C Black Lightning, a production version of the bike Rollie Free rode to break the AMA land speed record in 1948 on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Available only by special order, the standard Black Lightning was supplied in racing trim with a tachometer, Elektron magnesium alloy brake plates, racing tires on alloy rims, rearset foot controls, a solo seat and aluminum mudguards.

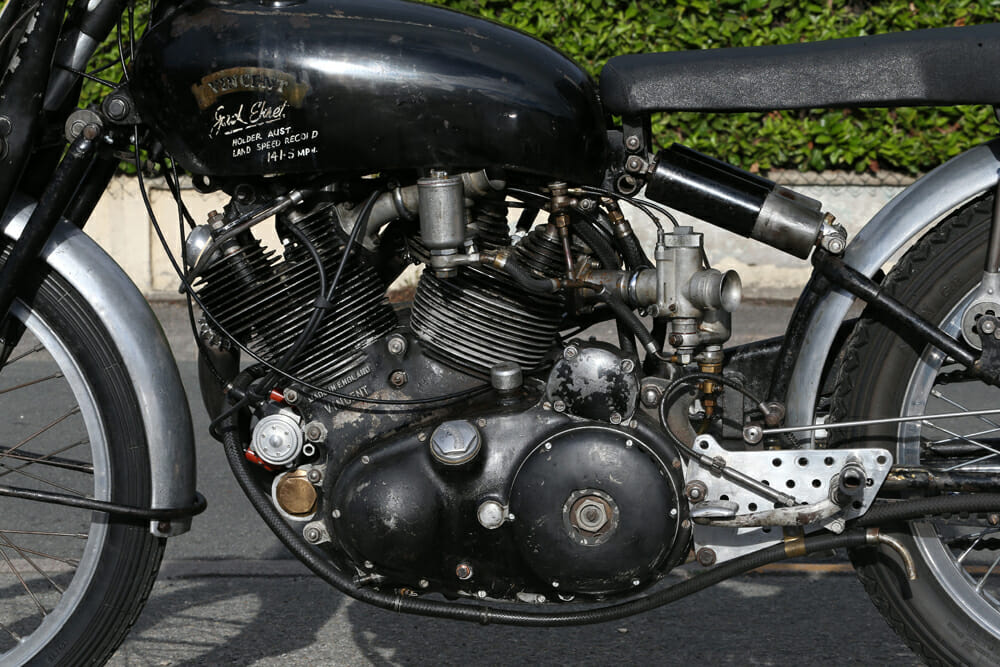

This reduced the Black Lightning’s dry weight to just 360 pounds versus the Black Shadow’s 458 pounds, complete with lights and a horn. The Lightning’s 998cc air-cooled, overhead valve 50° V-twin engine was given higher-performance racing components including Mark II Vincent cams with higher lift and more overlap, stronger, highly polished Vibrac connecting rods with a large-diameter caged roller-bearing big end, polished flywheels and Specialoid pistons delivering a 13:1 compression ratio for methanol fuel.

The combustion chamber spheres were polished, as were the valve rockers and streamlined larger inlet ports, blended to special adapters and fed by twin 1¼-inch Amal 10TT9 carburetors. The Ferodo single-plate clutch’s cover featured center and rear cooling holes, while the four-speed gearbox was beefed up to transmit extra power of at least 70 hp at 5600 rpm (versus the Black Shadow’s claimed 55 hp) and a top speed of 150 mph.

The Original Superbike

The Black Lightning’s genesis is the stuff of legend for Vincent enthusiasts, and essentially began with London Vincent dealer Jack Surtees, the father of Vincent factory apprentice John Surtees, the only man to win both the 500cc and Formula One World Championships. He’d been racing a Norton sidecar with some success, and in 1947 ordered a V-twin Vincent Rapide with special tuning parts. This engine was built at Vincent’s Stevenage plant alongside a second such engine, which was loaned to George Brown, Vincent’s experimental tester, whose ensuing bike became famously known as Gunga Din and was the test bed for the Black Shadow and Black Lightning.

First shown at London’s 1948 Earls Court show, the production Black Lightning caused a sensation despite its then-enormous $550 price tag plus a hefty $150 purchase tax (the average British salary in 1948 was about $415). It’s generally accepted that only 33 complete customer versions—all Series C except for one Series D model—plus Rollie Free’s first 1948 Series B prototype were ever built (together with anything up to 13 engines for installation in race cars), before production ended in 1952.

Today, the Black Lightning is perhaps the most coveted production motorcycle ever built. Only 19 of the bikes built are believed to still exist, so the astronomical values achieved at auction (like just happened in Las Vegas) on the rare occasions when one comes on the market, makes the unrestored ex-Jack Ehret three-owner bike with a glorious unchallengeable racing history, a rare and immensely desirable slice of motorcycle history.

The first two “Lightningized” engines for Surtees and Brown’s Gunga Din were numbered F10AB/1A/70 and F10AB/1A/71, respectively, and the special Shadow sold to U.S. dealer John Edgar in July 1948 was F10AB/1B/900. Subsequent Lightnings all carried the “IC” designation, and the third of these to leave the factory, F10AB/IC/1803, was sent to Sydney, Australia, in March 1949, and purchased by sidecar racer Les Warton.

From 1949-1952, six complete Black Lightnings plus one engine went to Vincent agents in Australia, the company’s second-largest export market after the U.S., with two more privately imported, one via Singapore. One was raced in 1949 by Sydney rider Tony McAlpine, who became virtually unbeatable in Unlimited class events aboard the Black Lightning, winning 12 major races from 13 starts.

For the 1951 European season, McAlpine decided to try his hand overseas, securing an AJS 7R for the 350cc class and finishing 13th in the Isle of Man Junior TT. In between races, McAlpine worked at the Vincent factory at Stevenage, and with the factory’s blessing, assembled his own Black Lightning with engine number F10AB/1C/7305 and frame number RC9205. This was completed on June 5, 1951, and tested on July 19 at Great Gransden airstrip alongside Gunga Din, hitting 130 mph in third gear and, according to McAlpine, out-accelerating Gunga Din by a clear 30 yards on each standing-start sprint run.

McAlpine’s final race in Britain before sailing for home was at Boreham Aerodrome, a very fast circuit, in a program that included an Unlimited race. For the meeting, Phillip Vincent invited McAlpine to ride Gunga Din, which he did with great verve, sliding speedway-style through the turns to demolish the field. McAlpine then sailed home, taking with him the new, unraced Black Lightning. He had no plans to return to Europe, but after receiving a sponsorship offer from Shell, plus the nomination as Australian representative for the TT, he decided to return for 1952. To save money and stay clear of injury, he didn’t race during his brief return to Australia, and put the Vincent up for sale.

The £500 price asked for the Black Lightning would have bought a couple of nice houses in Sydney at the time. One of the few riders with funds to buy the Lightning was car dealer Jack Forrest, a talented rider. At the 1951 Australian TT held at Lowood in Queensland in June, Forrest was the star of the show, winning the Junior race on a Velocette KTT and the Senior on a Manx Norton. He also raced a Vincent Black Shadow in the Unlimited class, and he was out in front in that race before a split fuel line sprayed methanol on the rear tire. Although he controlled the resulting skid, his race was over.

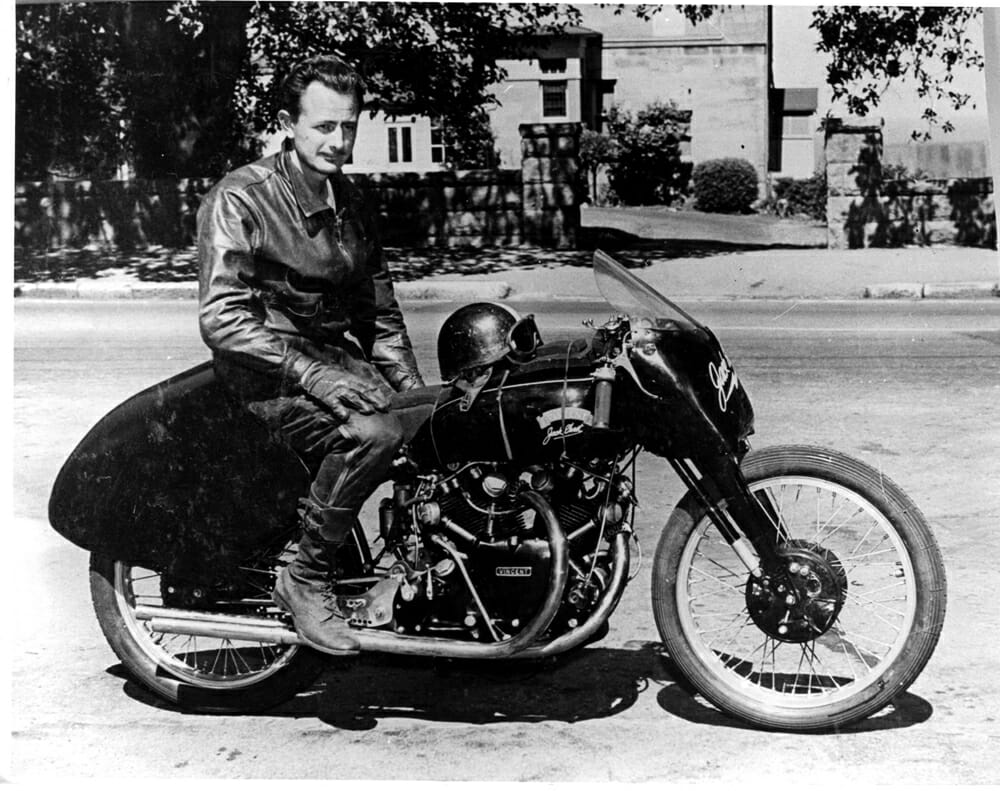

Forrest had now seen that a well-tuned Vincent on a fast circuit was superior to even the best Norton, so when the opportunity to acquire McAlpine’s Black Lightning came along, it proved irresistible. He bought the bike and raced it in the Australian TT at Bathurst in the Senior Unlimited TT, but crashed during the race, without serious injury and with mainly superficial damage to the bike. Nonetheless, the experience seemed to break his love affair with the Vincent. Forrest set out to acquire a new Manx Norton and placed the Lightning for sale with Sydney dealers Burling and Simmons. There it sat for months until bought by Jack Ehret, owner of two Sydney motorcycle shops. Ehret wasn’t exactly flush with funds, but knew that if he didn’t get hold of the Lightning, one of his racing rivals would. And so F10AB/1C/7305 found a new home, where it would remain for the next 47 years.

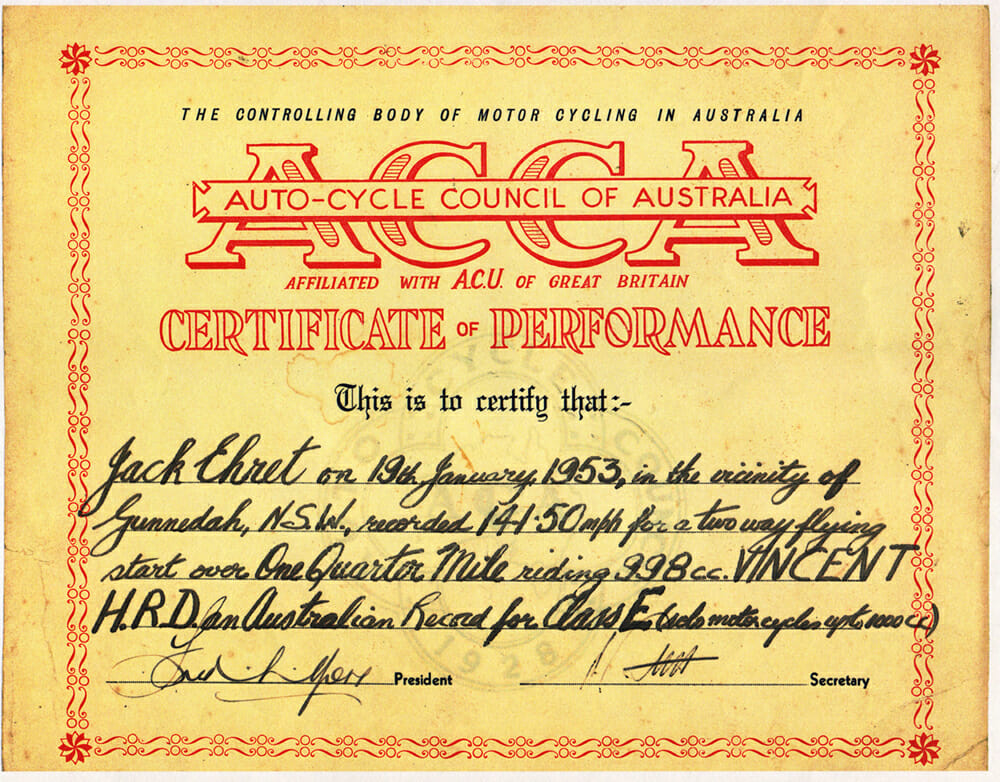

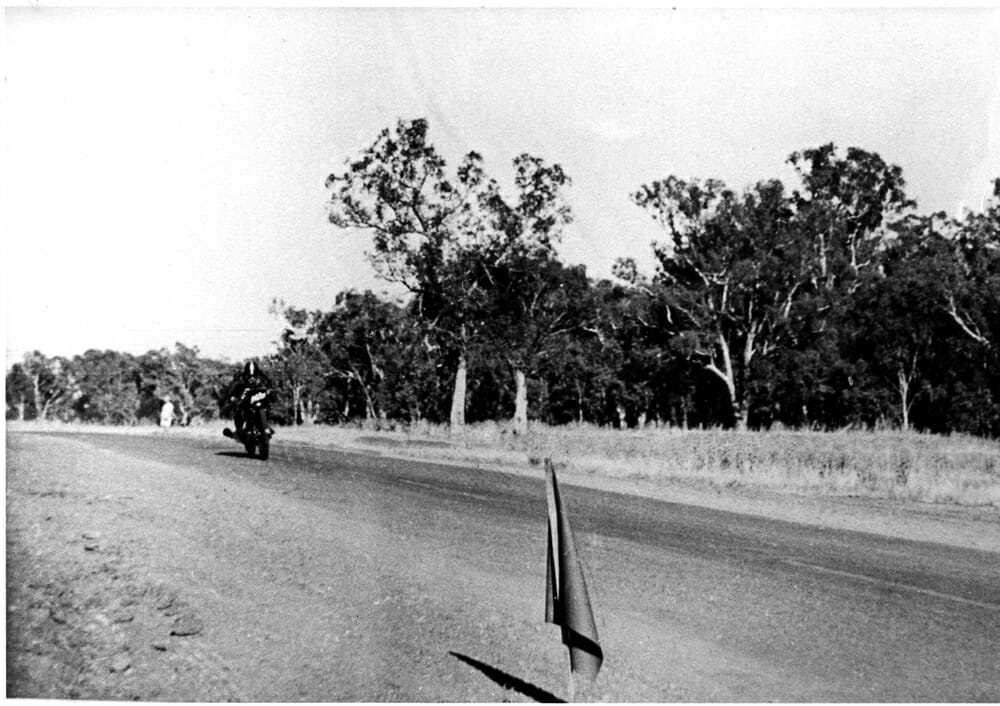

“Black Jack” Ehret’s first major outing on the Lightning was the Australian TT at the Little River circuit on Boxing Day 1952, where he finished second in the Senior Unlimited TT. At that time, the Australian Land Speed record was constantly under attack, so in January 1953, Ehret selected a remote stretch of road in western NSW to challenge Les Warton’s Vincent record of 122.6 mph. Despite a few problems, he averaged an officially timed 141.509 mph to smash the record. Ehret claimed the attempt cost him £1000-plus, but considered it well worth it in sales promotion for his business to earn the coveted certificate from the Auto Cycle Council of Australia.

Racing Gentleman Geoff

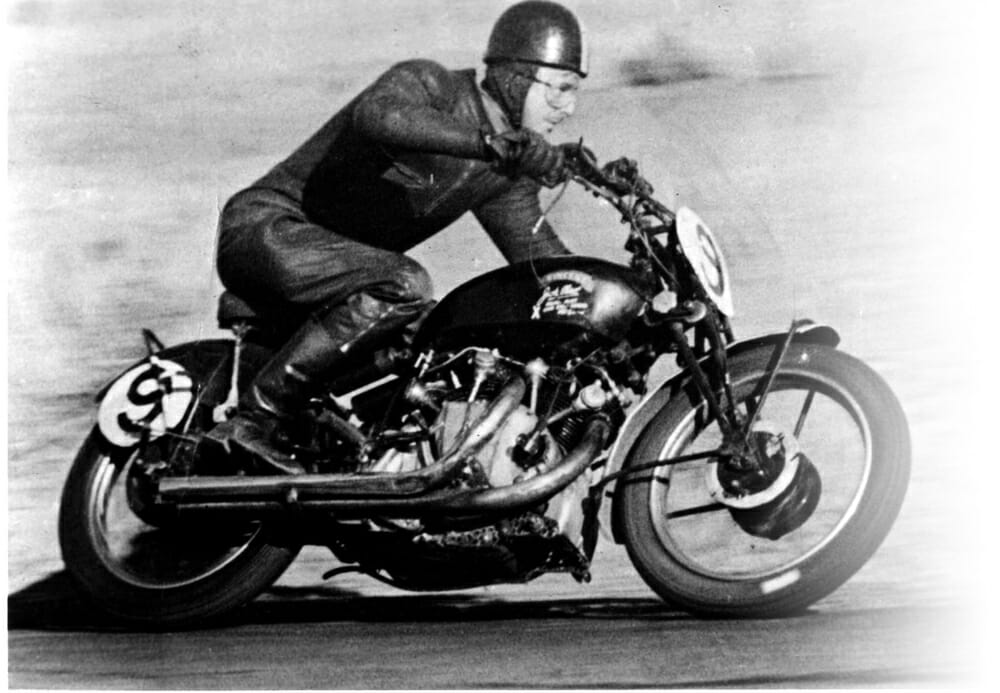

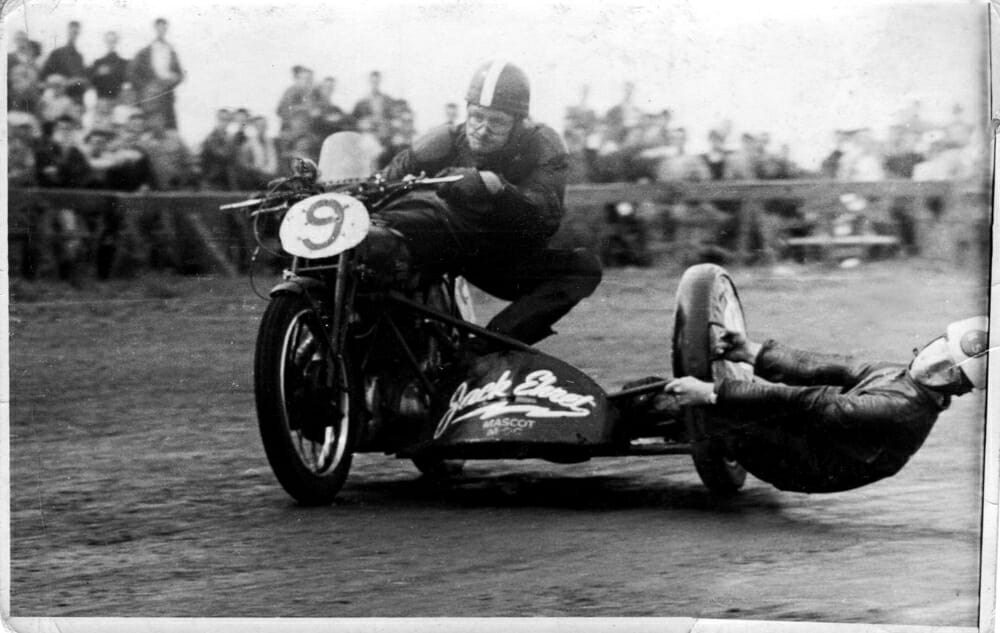

Over the next five years, Jack Ehret and the Black Lightning were regular fixtures at Australian road race meetings, with the Vincent appearing in both solo and sidecar guise, often in the same day, with Stan Blundell in the chair. Ehret and the Lightning wound up Australian Title points leaders in 1954 ahead of a host of famous names. Undoubtedly its proudest moment as a solo bike came at the much vaunted international meeting at Mount Druitt in February 1955, where 500cc World Champion Geoff Duke, visiting from England, was the star attraction with his works four-cylinder Gilera.

Duke had demolished the opposition in his previous starts on his Australian tour, but on his home track, Ehret was fired up for action, and fancied his chances in the Unlimited TT. Reporting on his tour in the British motorcycle press, Duke wrote: “Ehret made a poor [push] start in the Unlimited event, whereas I was first away, and piled on the coals from the beginning. Thereafter I was able to keep an eye on the Vincent rider approaching the hairpin as I accelerated away from it. Although he was unable to make up for his bad start, Ehret rode to such purpose that he equaled my fastest lap, and we now share the honor of being the lap record holders.” After this scintillating performance, Jack then bolted on the chair for him and Blundell to win the Sidecar race!

One win that had eluded Ehret was the Australian TT at Bathurst, but he put that right in Easter 1956, winning the Sidecar TT with passenger George Donkin. Perhaps with this goal achieved, Jack and the Vincent became less frequent competitors, and when Mount Druitt closed in 1958 the Black Lightning was mothballed for 10 years. In 1968, Ehret made a comeback of sorts at Oran Park, with the Lightning now fitted with 16-inch wheels and John “Tex” Coleman in the chair. Despite the long layoff, Ehret didn’t disgrace himself, finishing third in the Sidecar race. But a further decade passed before he brought the Black Lightning out for one more outing, again at Oran Park. By this time, the Vincent was in a different class—Historic—and Ehret demolished the field to win both his races by almost a complete lap. Its last appearance was at the Eastern Creek circuit in 1993, where Ehret lapped the entire field, winning both Historic Sidecar races passengered by his son John, then removed the chair for John to ride it in two solo races. According to Jack, the Vincent finished on the rostrum in 80 percent of the races he entered during his 40 years of racing it.

Thereafter, the Lightning began a long hibernation in a Sydney shed while Jack Ehret started a different life running nightclubs in the Philippines, before it was put up for sale in 1999, not long before Ehret passed away unexpectedly on July 7, 2001, aged 78.

The new owner was Franc Trento, owner of Melbourne-based EuroBrit Motorbikes, and a noted Vincent enthusiast who fortunately determined that the Lightning would not be restored, but would be kept in exactly the same “as used” condition he’d acquired it in. It had been returned to its original specification with 21-inch front and 20-inch rear wheels, with a very rare big-fin drum front brake and a double-sided rear one for sidecar use. Far from becoming a static piece, the Lightning was regularly displayed, including taking to the track at the Broadford Bike Bonanza in 2009 and 2010. In 2014, Trento sold the bike to French collector Nicolas Dourassoff, who shipped it to France, where local Vincent expert Patrick Godet recommissioned it. But after barely three years of ownership, in January 2018, Dourasoff offered the Vincent for sale at the Bonhams Auction in Las Vegas, where it went under the hammer for $929,000 incl. buyer’s premium, making it the most valuable motorcycle ever sold at a public auction at around twice the price that Dourasoff paid Franc Trento for the bike in 2014. The winning bid was placed by Australian collector Peter Bender, owner of a prized collection located in Tasmania of British motorcycles led by an array of Brough Superiors, which the Ehret Vincent has now joined. CN

A rare moment indeed—riding Jack’s Vincent

In its 68-year existence, Vincent Black Lightning engine number F10/AB/1C/7305, frame number RC 9205 has so far clocked up 8587 kilometers (the kilometer speedo was fitted from new in “European” specification) and virtually every single meter has been covered in pursuit of glory. And thanks to its then owner Nicolas Dourassoff’s generosity, I added around 50 more of those kilometers myself after he asked me to come and test it!

To be invited to ride a bike such as the Ehret Vincent was an act of huge generosity, as well as implied trust. My two dozen laps came at the Circuit Carole on the outskirts of Paris, to which Nicolas brought the battle-scarred warrior, recommissioned for use by French Vincent guru Patrick Godet, for me to ride. Godet also brought along a recently built, 100-percent authentic Black Lightning Replica, which he’d created for customer Peter Fox. Peter had already covered 1200 street miles on it, pronouncing it “huge fun, and incredibly impressive once you get it revving, when it feels like you’re being pulled along by a huge bungee cord!”

Thanks, Peter, I couldn’t put it better myself, for that is indeed the impression you get on the Ehret Vincent once you see its Smiths Chronometric rev-counter’s needle track its way with traditionally jerkiness to the 3800 rpm mark, whereupon the bungee cord releases and you’re swept to what must have been unthought-of speed by mid-20th century standards.

Nothing much happens below those revs, though, so you have to coax the engine into meaningful action with a dab on the Ferodo clutch’s light-action lever. But from that access point to its inbuilt poke onwards, the paragon of performance that all the Black Lightning’s records and race victories proclaim it to be, makes itself apparent. In no time at all the revcounter’s showing the 6000 rpm mark, at which point you must stab the extended gearlever downward with your right foot to hit a higher ratio of the four available. There are such massive amounts of torque even by today’s standards that the Vincent just lunges forward in the next higher gear when you get back on the throttle again, noting as you do so that its action seems unaccountably smooth, considering how worn the self-evidently ancient cables sprouting from the right handlebar and leading to the twin Amal 10TT9 carbs, appear to be.

That’s because, in recommissioning this racer for track action in accordance with Nicolas Dourassoff’s belief that historic bikes should be seen and heard in action, not stuck in a garage on permanent static display, Patrick Godet has been at pans not to destroy the truth of time.

“Once Nicolas decided to preserve the bike in its current state, and not restore it—which was 1000 percent the right decision—I wanted to make sure that any new parts I fitted were as least obvious as possible,” he says. “But to make it safe to be ridden took quite a lot of work, because the engine parts were very worn, and the crankshaft had been repaired in a funny way. We stripped the bike totally, and rebuilt it using the original spec parts we have manufactured using the original Black Lightning factory drawings that we’ve obtained. But they’re all inside where you can’t see them, so while the throttle and brake cables may look old, all the internal wires are brand new, to give a smooth action. We’ve also converted it to running on petrol rather than methanol—we have much better fuel available today than they did back then.”

The crankcases are the original ones, with the main bearings re-sleeved. New pistons, liners, valves, dual valve springs, Mark II Vincent cams, cam followers and oil pump are fitted to the bike. The original parts have all been saved. The original 20-inch rear wheel has been replaced by a 19-incher, as 20-inch racing tires are no longer available. Now shod with a rear Avon GP tire matched to a front 21-inch ribbed Avon Racing tire, the Ehret Vincent tracked well through Carole’s infield section, with good grip delivered exiting both of its hairpin bends, which on most race bikes ask for bottom gear. Not the Lightnings, though, thanks to their reserves of torque and the way they break into a gallop very quickly in second gear once you’ve straightened up.

When that happens, you find yourself thundering past the Yamaha YZF-R6 that have out-maneuvered you in the infield section, only to let them fly past you once again when you anchor up early for the next hairpin. The brakes on the Vincent are easily the worst thing about riding it, and you need lots of respect for your braking markers, because there’s little held in reserve. Instead, what never works very well to begin with gets progressively worse as the pair of tiny 7-inch single leading-shoe drum brakes fitted at each end fade massively. These carry brand-new Godet replica aluminum brake plates rather than the original Lightning magnesium items, which are too fragile to be safe. Probably no single aspect of motorcycle engineering has improved so much in the past 68 years as brakes, and for a 150-mph motorcycle the Vincent’s stoppers are definitely on the weak side.

The ex-Jack Ehret Vincent Black Lightning is more than just an ultra-desirable collector’s item, providing a window on the refined but still raw-edged performance that Philip Vincent’s motorcycles delivered more than 60 years ago. Let’s hope its new owner rides and enjoys it, like his predecessor, rather than wrapping it up as the mechanical objet d’art it undoubtedly is.

NOTE: Special thanks to Old Bike Australasia editor Jim Scaysbrook for supplying the historical data in this article and the period photos. CN

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine

Click here for more Ducati motorcycle reviews and news.