Alan Cathcart | December 9, 2017

A failed Moto2 racer has turned into a true gem of a road sportbike. Meet the Vyrus 986 M2 Strada.

Like a Bimota Tesi, only better. The Vyrus has come straight from the racetrack to give you the ultimate street riding experience.

Like a Bimota Tesi, only better. The Vyrus has come straight from the racetrack to give you the ultimate street riding experience.

Sticking the “racer with lights” label on a refugee from the racetrack isn’t always a passport to street-legal satisfaction. But when you’ve had six long years to figure out how to go about it, the chances are good that you might get it right.

That’s how long it’s taken Vyrus virtuoso Ascanio Rodorigo to do just that with the Moto2 racer he first unveiled in January 2011, with the promise that he’d produce a homologated street version in due course—and now at last he has.

Rodorigo is the proprietor of Italian boutique bike builder Vyrus Divisione Motori, the so-called Clinica Moto [aka bike clinic] located just a stone’s throw from the Bimota factory on the outskirts of Rimini.

There, for the past 14 years, he and his like-minded quartet of fellow craftsmen have patiently created a succession of two-wheeled works of art represented by the over 150 examples of the high-priced hub-center Vyrus sportbike they’ve constructed there during that period under the pura follia tecnologica banner—and it is indeed a fact that they represent two-wheeled technology truly gone mad!

Photography by Kel Edge

But works of art? Really? Look, if the late Massimo Tamburini was the Michelangelo of Motorcycles, then his 54-year-old disciple Ascanio Rodorigo is the Picasso of bikes, as confirmed by just one look at any of the deconstructed examples of two-wheeled cubist sculpture that the Italian engineer has produced under the Vyrus name since founding the company in 2003.

Like the Richard Rogers-designed Pompidou Art Centre in Paris, which displays its pipes, drains, conduits and air-con ducts on the exterior of its walls for all to see, the series of surreal-looking hub-center Vyrus models exclusively powered until now by Ducati desmo V-twin motors in various configurations and capacities, all seem to wear their technology on the outside, in plain view.

As the 21st century evoluzione of the avantgarde Tesi 1D hub-center street bike, of which Bimota built just 417 customer examples during five short years from 1991 to 1995. That included 51 fitted with the 400cc air-cooled desmodue motor for sale in Japan—each Ducati-engined Vyrus variant represents a technological tour de force that’s even more minimalist and certainly more aesthetically appealing than the slab-sided Tesi 1D, whose all-enveloping styling covered up the trick tech its design embodied.

But as its designation indicates, the new Vyrus 986 M2 represents a sideways step in a completely different direction by Rodorigo. As the first Vyrus model to be powered by a four-cylinder engine (and a Japanese one, too), it’s also the first in the firm’s 15 years of existence to feature anything other than a Ducati desmo V-twin motor.

The looks may not be for everyone, but you cannot deny the exquisite engineering that goes into a Vyrus.

The looks may not be for everyone, but you cannot deny the exquisite engineering that goes into a Vyrus.

The chance to ride the Tesi’s modern-day successor was too good a chance to miss, especially as this was the first time I’d ever ridden a Vyrus on the street, rather than a racetrack—and particularly since this Honda-engined 600cc street bike is the smallest-capacity Vyrus model that Ascanio Rodorigo has yet built. Can less truly be more?

Apparently so. Hopping aboard the Vyrus 986 M2 brought the memories of many past Bimota rides flooding back, even if it felt much smaller and more purposeful than the bigger, more boat-like Tesi 1D that I raced 25 years ago.

Its riding position felt improbably comfortable and comparatively normal, without your hands being too close together as on some other hub-center bikes, thanks to the absence of a “proper” set of forks and the triple-clamps they’re harnessed in. The vestigial painted bodywork helped add to the sense of minimalism, but not at the expense of wind protection—speeds of up to 120 mph, as indicated on the digital speedo on the stock Honda dash, didn’t deliver excessive windblast, thanks to the small but effective screen.

Yet despite having such a short wheelbase the Honda-engined Vyrus has a surprisingly spacious riding position that’s really welcoming for people of any stature—it turns out Ascanio gets both taller and shorter riders to sample any of his designs, and each must be comfy on the bike before he signs it off. Moreover, the seat is deliberately narrowed where it meets the fuel tank-cum-airbox shroud, and despite its tall 32.8in height, this allowed the 5’10” me to place both feet flat on the ground at traffic lights.

That swingarm is massively beautiful.

That swingarm is massively beautiful.

Everything about the Vyrus seems refined, delicate even, in its design and function, although to begin with I struggled to remap my mind processes to suit, and adjust to doing things differently aboard such a bike, as you must.

Low-speed maneuverability in the several tight turns along the Strada Panoramica looking out over the Adriatic Sea was good, with none of the ungainliness of most other such hub-center bikes that I’ve tried, including the Tesi which I vividly remember was not at all at home in slow corners—or bumpy ones.

By contrast, the steering of the Vyrus seems light but deft, without being over-sensitive, just controllable, and indeed the whole bike seems less remote, more direct-steering and predictable than “my” Tesi did 25 years ago. You feel much more involved with it, and yet there’s no sense of instability in spite of the light steering.

After a few miles of gradually picking up speed, my mental computer was rebooted, and I recalled the mindset you must adopt to get the best out of any hub-center motorcycle. Which is, hold the ‘bars lightly, be delicate with steering inputs, and don’t be afraid to stay off the brakes until what seems fatally late. Then, when you do finally decide to stop, don’t be reticent in grabbing a big handful of front brake. Then just keep squeezing the lever hard as you tip into the apex of a turn, while still scrubbing off speed. The separation of steering from suspension functions is the biggest asset of hub-center front ends—only that you must first convince yourself that you can, indeed must trail-brake deep into turns, then do it!

The twin Brembo 320mm front discs and their Monoblock calipers gave phenomenal bite in slowing what is a pretty light bike down very hard from very late, and single-digit operation of the lever tucked right down below the handlebar on this racetrack refugee became a matter of norm. But I needed two digits—the forefinger of each hand, in fact—to reach down into the carbon recesses to turn the ignition key on or off that’s hidden beneath the carbon lid behind the steering head.

Braking hard brought more Bimota memories, of the way the Tesi would stay flat and balanced whenever I braked deep into a turn. Once you come to terms with the fact there’s essentially no front-end dive, you realize that the suspension keeps on working even though you’re braking so hard, because the Vyrus is almost oblivious to the weight transfer this delivers, especially your own.

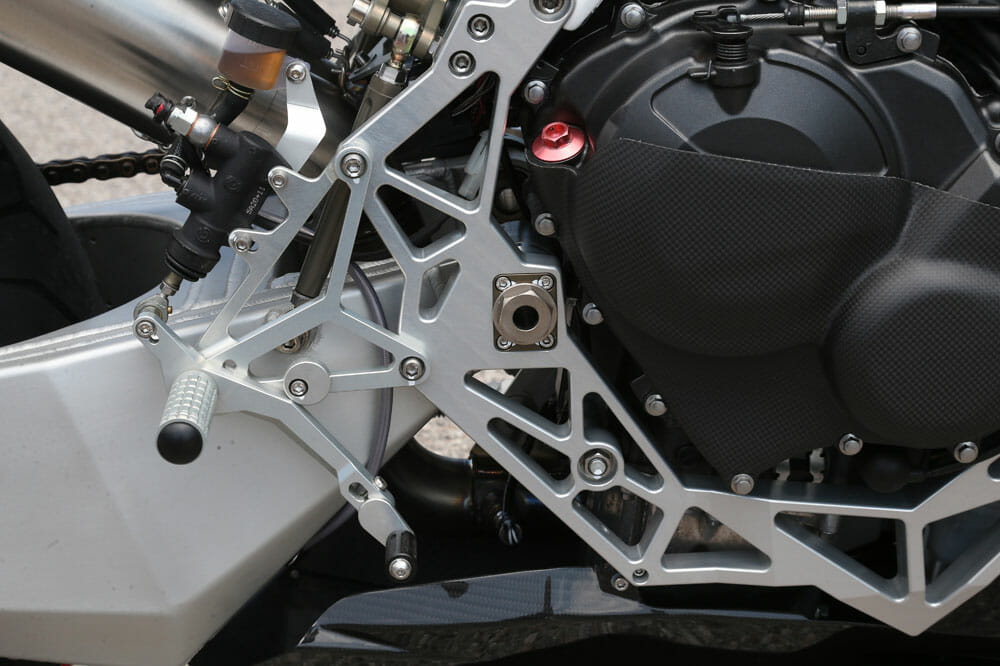

The attention to detail with parts like the rearsets is stunning.

The attention to detail with parts like the rearsets is stunning.

And once you do get dialed in to the reduced braking distances on offer, your increased confidence will allow the Vyrus to carry huge amounts of turn speed, while still eating up any bumps encountered on the angle, either on or off the brakes. That’s why Ascanio has fitted a wide 3.75-inch forged aluminum front wheel to the bike, rather than a more commonplace 3.50-inch one, in order to try to increase the contact patch area for better grip in turns. “I’d fit a five-inch front wheel if I could get one!” he declares.

As with previous Vyruses (Vyri?) I’ve ridden, this bike is so confidence inspiring and well balanced, with seemingly no sensitivity to any kind of weight transfer, either under braking into the turn or accelerating hard out of it, that there seems no limit how hard you can push it in corners. Well, only one, which is that this kind of treatment will quickly wear out as grippy a tire as the excellent Pirelli Diablo Supercorsas fitted to the Vyrus. The extra velocity entering turns you get from being able to brake so late gets scrubbed off hard, putting the front tire under strife—I ended up racing the Tesi with a 125GP rear tire on the front in longer races to try to get the tire to last, so Vyrus owners should be prepared to have to fit new front rubber as often as the rear.

What a shame such a beautiful (and expensive) bike must be delivered with the same dash and switches as a standard Honda CBR600RR that costs less than three times as much.

What a shame such a beautiful (and expensive) bike must be delivered with the same dash and switches as a standard Honda CBR600RR that costs less than three times as much.

You can get hard on the gas really early while still leaned over—as soon as you let off the brakes you should cane the throttle—and the Vyrus was very stable under power in spite of being so short.

Ride quality was excellent, too—not only surprisingly good for a sport bike, but compliant and effective in smoothing out road rash, and for sure much more so than the stiffly sprung shocks we had to run to stop the Tesi weaving at speed, a problem I grappled with all the years I raced a hub-center bike that was so hyper-sensitive to setup, with bump steer a constant issue that was sometimes impossible to dial out.

Where the Vyrus also excels compared to its Bimota ancestor is the ease with which I could flick it from side to side along the Strada Panoramica. The Tesi was always hard work to lift from side to side at any sort of speed, whereas the smaller Vyrus felt much more agile and responsive. The quite radical geometry, with just an 18-degree effective head angle and 3.7in of trail (adjustable up to six degrees wider from there, and from 3.1-4.1in of trail), allowed it to change direction faster than most bikes of comparable size, thanks also to the ultra-short 53.1in wheelbase.

Yet that steep head angle didn’t result in any significant instability as a tradeoff for that quick, agile handling, although to begin with I found myself over-steering into the apex of a turn, because I was subconsciously treating the Vyrus like a ‘normal’ Supersport Honda, which isn’t exactly heavy in changing direction but is slower-steering than the Vyrus. Mental adjustment did the job.

Okay, but what now? Where does the two-wheeled Vyrus (virus?) that’s transmitted when you ride the bike, and gets under your skin to attack your preconceptions, go from here?

Once you reprogram your brain, the Vyrus will carve canyon road with the best of them (at the expense of front-tire life).

Once you reprogram your brain, the Vyrus will carve canyon road with the best of them (at the expense of front-tire life).

“It’s an important fact that Kevin Schwantz held the 500 GP Assen lap record on the most demanding grand prix circuit for 10 years,” says Ascanio with the fervor of a true believer. “This tells you that we’re standing still—even with better tires and more horsepower, they still couldn’t beat his time. So, in my opinion, this just one more confirmation of what we already know, that the motorcycle industry has been running up and down in the same place for a long time. Although they continue to develop ordinary telescopic forks, from 32mm 50 years ago up to 50mm today, the fact is you can’t go faster unless you put on better tires or develop a more powerful engine—the actual design of a motorcycle has stood still. It’s our objective to try to persuade people to take a fresh look at two-wheeled chassis design, and the Vyrus is the result.”

The Vyrus 986 M2 is an exquisitely conceived, finely detailed and brilliantly executed motorcycling masterpiece, a genuine two-wheeled work of abstract modern art that Picasso himself would have been proud of. The fact that it proved to work as well dynamically as it looked aesthetically was almost an added bonus—so good luck, Ascanio, in your mission to change the two-wheeled world.CN

All the way from Moto2

The Vyrus was designed to compete in the Moto2 class inaugurated back in 2010 as a replacement for 250 GP’s two-strokes, complete with a 600cc four-cylinder Honda four-stroke control engine derived from the CBR600RR street bike.

Bradley Ray showed not just his but the Vyrus’ talents in the extremely competitive CEV Moto2 series, until the funds ran out.

Bradley Ray showed not just his but the Vyrus’ talents in the extremely competitive CEV Moto2 series, until the funds ran out.

Seizing the opportunity to demonstrate the worth of his design in what was promoted as being a chassis builders’ class, Ascanio created the 986 M2 racer to demonstrate in head-to-head racetrack competition the validity of his design concepts on the level playing field represented by the control engine formula, meaning engine performance is theoretically equal among all contenders.

But while like many others Rodorigo initially hoped the Moto2 series would provide a showcase for alternative frame designs, that’s not the way it’s turned out. In launching the 986 M2 as a pure Moto2 racebike in 2011 he’d hoped to forge a partnership with one or more Moto2 race teams— but such alliances proved hard to come by. Race team directors are the most pragmatic and conservative of people, given that any team’s sheer existence is dependent on sponsorship generated by results which allow them to survive and prosper. This means that what works well today for another team in turn becomes must-have material for the others (how else to explain the fact that Moto2 is now almost entirely made up of Kalex chassis?) leading to a general reluctance to experiment with anything out of the ordinary, rather than risk being left behind by using something novel, but unproven like the Vyrus.

Which explains why the Vyrus 986 M2 ended up making its racetrack debut not at a MotoGP race, but in the opening round of the 2012 Trofeo Italiano Amatori club racing series at Misano, ridden by Ascanio’s son Davide Rodorigo, who finished 33rd in the 600cc class, one place behind his teammate Marco Chiancianesi, the Swiss-Italian property developer who’d shortly acquire Bimota the following year.

Rodorigo did a couple more rounds on Dad’s racer, which was then parked up for a year while Ascanio kept searching for anyone to team up with. He found an ally in the shape of Stefano Caracchi, the son of the co-founder of NCR and a former works Ducati rider and 250GP racer. He’d been running his own race team in the Italian Superbike series, and became fascinated by the technical innovation of the Vyrus. Caracchi arranged to run the bike in the six-round 2015 Spanish CEV Moto2 series, Dorna’s feeder class for the MotoGP support series, and recruited 17-year old Brit Bradley Ray—today a regular top 10 finisher in BSB on a privateer Suzuki GSX-R1000—to race the bike.

Ray’s racer. Not much has been changed between this and the production bike.

Ray’s racer. Not much has been changed between this and the production bike.

Though he’d never before ridden anything without telescopic forks, Ray took to the Vyrus immediately, finishing 23rd out of 40 starters in the opening round of the series in Portimao, improving to 16th in the next race. But the pressures of trying to go racing competitively while also earning a living building customer bikes began to tell, and by midseason Ray had returned to England, while Ascanio finally began working on what he’d had so many requests from customers to make—a street version of the Moto2 Vyrus.

“Our customers had seen that our M2 motorcycle is easy to ride, and steers fast and easily with great turn speed—but they all wanted to have an example with mirrors and lights that they could ride on the street, not a racer,” says Ascanio. “So, we understood we must obtain homologation, but the process for this is very long, so it wasn’t until the end of November 2016 that we achieved this. But now we can sell the 986 M2 Strada anywhere in Europe as a fully homologated streetbike, and this makes it easier to register the bike overseas, too.”

The price for a complete Strada model with a brand-new stock CBR600RR donor engine is $44,954 on the road not including tax, fully built up with the key in your hand, and full EU homologation, while $33,102 gets you a complete bike minus engine, but in kit form. In Corsa race guise but without a motor the cost rises to $64,008 upwards, depending on specification.

“There’s a huge list of options, so these are only guide prices,” says Ascanio. “No two Vyrus motorcycles have ever been the same as one another, so the list price is just a starting point, leaving each customer to individualize his bike.”

Vyrus has already constructed and delivered 28 street-legal examples of the 986 M2, is currently working on another six under deposit, but will cap production at just 50 bikes, meaning there are just 16 still available.

Ascanio may come across as a bit of a mad scientist, but his methods have taken race wins all over the world.

Ascanio may come across as a bit of a mad scientist, but his methods have taken race wins all over the world.

“The problem is that Honda is going to stop making this 600cc motor quite soon,” says Ascanio. “But we are already investigating other engines to form the basis of the next evolution of this model.” Which would presumably account for the MV Agusta 800 triple motor sitting on top of a workbench in Vyrus HQ with measuring equipment all around it. “No comment!” said Ascanio.

Besides the avantgarde hub-center technology which essentially represents a Tesi done right, the dramatic, angular, modernist Vyrus styling entirely executed in carbon fiber is also the work of Ascanio himself, with close help from young Japanese female designer Yutaka Igarashi www.id-performance.com and ex-Ducati stylist Sam Matthews, formerly Pierre Terblanche’s right hand at the Bologna factory, who later worked for Citroën in Paris.

“We finalized the design at long distance, with Sam making CAD drawings in France, and me interpreting them into a full-size clay model, then e-mailing him photos of the result!” says Rodorigo.CN

|

SPECIFICATIONS: Vyrus 986 M2 Strada

|

|

Engine:

|

Liquid-cooled DOHC 16-valve transverse inline 4-cylinder 4-stroke with offset chain camshaft drive

|

|

Displacement:

|

599cc

|

|

Bore x stroke:

|

67 x 42.5mm

|

|

Compression ratio:

|

12.2:1

|

|

Clutch:

|

Wet multi-plate

|

|

Transmission:

|

6-speed

|

|

Chassis:

|

Twin aluminum double inverted Omega frame spars holding engine as fully integrated chassis component, with 7020 aluminum sub- frames

|

|

Front suspension:

|

Aluminum hub-center swingarm with horizontally-mounted YSS double-rocker shock and rising rate pushrod linkage

|

|

Rear suspension:

|

Strutted aluminum swingarm pivoting in crankcases and frame spars, with horizontally-mounted YSS shock operated by rising rate pushrod link

|

|

Front brake:

|

Dual 4-piston Brembo M4.32 Monoblock calipers, dual 320mm Brembo T-Drive steel discs

|

|

Rear brake:

|

2-piston Brembo caliper, 220mm Brembo steel disc

|

|

Front tire:

|

120/70-17 Pirelli Diablo Rosso II

|

|

Rear tire:

|

180/55-17 Pirelli Diablo Rosso II

|

|

Rake:

|

21°

|

|

Wheelbase:

|

53.1 in.

|

|

Seat height:

|

32.1 in.

|

|

Fuel capacity:

|

2.9 gal.

|

|

Weight:

|

332 lbs. (oil, water, no fuel, claimed).

|

|

MSRP:

|

$44,954 (as tested)

|

Click here for all the latest Racebike news.