Larry Lawrence | February 21, 2017

Photos by Henny Ray Abrams

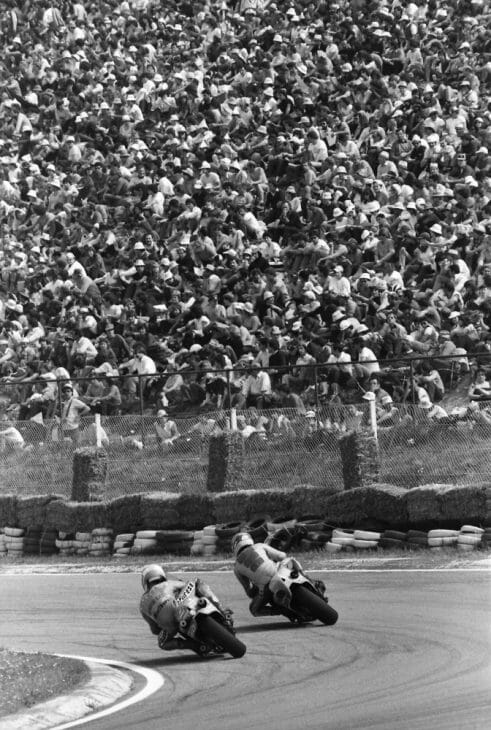

During the 1970s the Imola 200 became one of the biggest road races in the world, matching, and in some cases surpassing, the Daytona 200 in terms of factory participation. In its heyday, the Imola 200 attracted 140,000 fanatical spectators and drew nearly every top road racer of the era. The race had a colorful history with all the American riders who participated coming home with stories of rabid Italian fans, trigger-happy police, big-time paydays and welcoming locals.

The Daytona 200 reached its zenith of worldwide popularity in the early-1970s when international riders and factory and semi-factory entrants from numerous countries packed the huge field. Airliners were chartered bringing over hordes of European fans, journalist and photographers to watch their heroes taking on America’s best while railing around the famous high banks. As a bonus the Euros got a little late-winter Florida sunshine in the process.

Francesco “Checco” Costa, the dean of Italian race organizers, saw an opportunity in the Daytona phenomenon. He came up with the brilliant plan of bringing together the top riders from the Grands Prix, European, American and Italian championships to race together in the Imola 200. Inaugurated in 1972, the Imola 200 was billed as Europe’s Daytona.

Imola is a classic European circuit situated not far from the Adriatic Coast. Its three-mile plus length featured elevation changes, tight to ultra-fast turns and the flat out Tamburello corner – nearly a half-mile long where, like at Daytona, drafting games were played out at 180 miles per hour.

Attracted by generous start money and race purse, the Imola 200 kicked off with a bang in 1972 with an impressive racing line-up, which read like a who’s who of racing at that time. Italy’s hero Giacomo Agostini on the factory MV Agusta and his leading countrymen Walter Villa (Triumph) and Bruno Spaggiari (Ducati), along with top Brits such as John Cooper on the factory BSA, Paul Smart teammate to Spaggiari on the works Ducati, Phil Read and Peter Williams on the John Player Nortons, Helmut Dahne on a factory BMW and America’s sole entrant Daytona 200 winner Don Emde who rode a borrowed Norton after his Yamaha two-stroke was banned from the race. There were also factory entrants from Moto-Guzzi and Laverda as well as supports teams from Honda, and Kawasaki.

Ducati took its big home race as an opportunity to get back into racing after several years’ absence. The Italian company came loaded with specially built 750 SS machines for Spaggiari and Smart.

In the race Agostini broke away early but his MV didn’t last and it was Smart and his veteran Italian teammate Spaggiari battling for the lead the rest of the way. In the end it was Smart taking the win ahead of Spaggiari. Walter Villa was third on a Triumph. The 70,000 fans turned into a happy mob thrilled to see Ducati back with such success.

“They put our bikes in this big glass-sided truck and us on the top and that evening we had a grand tour around Bologna in a long procession of cars honking their horns and waving flags,” Smart recounted. “We stopped for what was to be minute outside the railway station, but thousands and thousands of people surrounded us and we just joined in the party. I was still in my leathers and so tired and jet lagged, but there was no way you were going to get any sleep at this party. It seemed and entire city came out to celebrate this glory for Ducati, Bologna and Italy.”

The race really blossomed in 1973. The two-stroke restrictions were lifted and the young Fin Jarno Saarinen, fresh off his victory in the Daytona 200, took the win over an amazing field on his factory Yamaha 350. A month later Saarinen and Italian Renzo Pasolini met with tragedy at Monza when the two died in a senseless pileup caused after track officials ignored warnings of oil on the circuit.

A host of AMA riders competed in Imola in 1973. Yamaha factory teammates Kel Carruthers (also manager of the team) and Gary Fisher decided to go at the last minute.

Massive crowds showed up to watch Italy’s best race against a mix of leading road racers from across the world.

The 1974 Imola 200 was a classic with Kenny Roberts making his first international race appearance. Agostini, like Saarinen the year before hot off a Daytona win, beat Roberts and the 120,000 Italians went into a state of euphoria. They also would long remember their first glimpse of the fast-rising young American star who would go on to become three-time 500cc Grand Prix World Champion.

Agostini’s 1974 victory put the Imola 200 over the top. A year later the race reached its zenith when an estimated 140,000 spectators flooded through the gates of the circuit. American Steve Baker finished third to Johnny Cecotto and Patrick Pons.

“It was my first experience with European racing,” Baker said. “The Italians were so friendly and into racing. We stayed in this Bed and Breakfast and the owners allowed to work on the bikes in the kitchen. The track was hilly and challenging sort of like Laguna Seca on a larger scale. I remember being impressed at how well-groomed the place was and of course the crowd was 100 feet deep all the way around the track.”

Baker came back and won Imola in 1976 and combined with the Match Races and the Paul Ricard 200 in France (part of the short-lived AGV Formula 750 World Cup with Daytona and Imola) he came home with over $200,000 in earnings.

Kenny Roberts finally took the victory at Imola in 1977 and would go on to join Cecotto as a three-time winner of the prestigious event. When Roberts made his international debut at Imola three years earlier he said the thing that really stuck in his mind was the mass of people and Kel Carruthers telling him to ride through the crowd back to the pits at the end of the race and whatever he did not to stop.

“It was an eye-opener for me,” Roberts said of Imola. “Up to that point my life pretty much consisted of trying to chase down some Harley at a dusty old flat and here I was racing in front of what seemed like a million people who were all waving the entire way around the track as Ago and I battled for the lead. It’s something I’ll never forget.”

Imola, while profitable for the U.S. riders, was not without tragedy. American up-and-comer Pat Evans died as the results of injuries suffered in the 1978 edition. Even though the track was relatively safe by 1970s standards there were still very high-speed sections closely lined with Armco covered by just a thin layer of haybales.

By 1979 the powers that be decided to move the Italian round of the World Formula 750 Series (of which the Imola 200 had become a part of) to Mugello and the Imola 200 was not held. Mugello didn’t have the atmosphere of Imola and the Italian fans didn’t support the race. The 200 came back to Imola in 1980, and in spite of the fact that riders like Marco Lucchinelli, Kenny Roberts and Eddie Lawson were among the winners of the race in the ‘80s, the momentum was lost and the 200 never again gained the prestige it held a decade earlier. Lawson’s win in 1985 marked the end of the classic Imola 200.

Imola, like Daytona, is likely to never again gain the popularity it held during its zenith. In a simpler time when all it took was a dream and little extra money to bring the world’s best riders together.